Do you identify as an Australian Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander?

Do you identify as an Australian Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander?

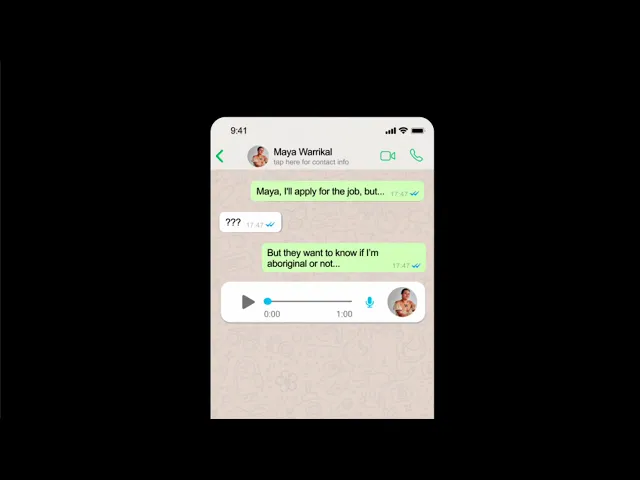

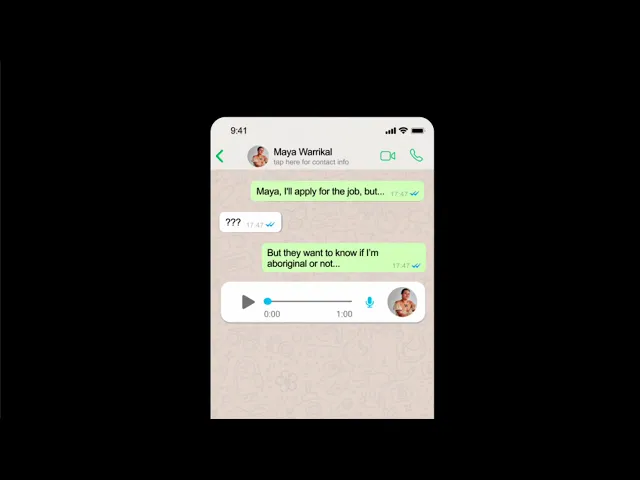

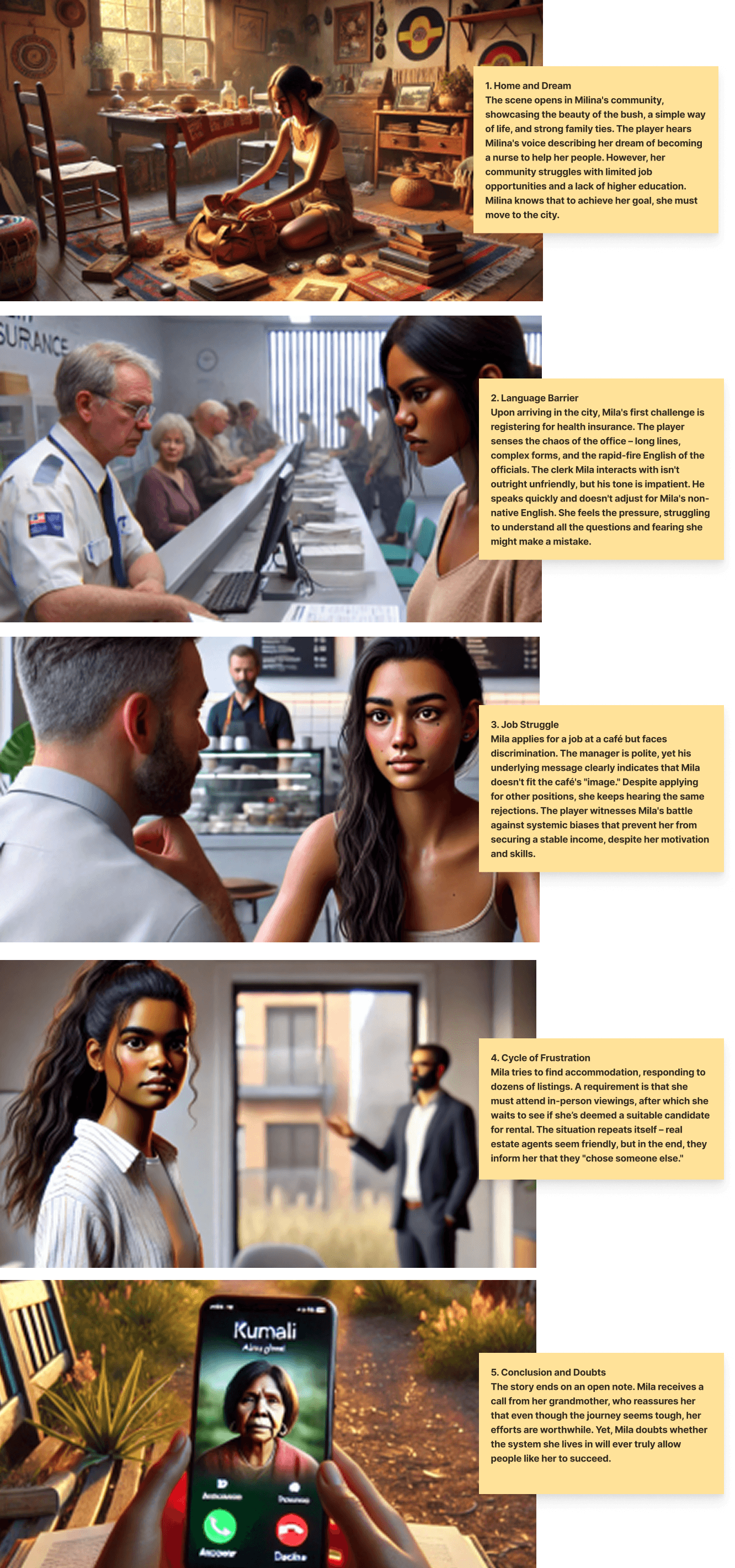

Imagine this: you’re an Aboriginal applicant in Australia, about to apply for a job. Before you can even show your skills, the hiring form asks you to declare your identity.

What feels like a routine question for most people suddenly becomes a moment loaded with doubt:

“Should I say it? Will it affect my chances? What if it changes how they see me?”

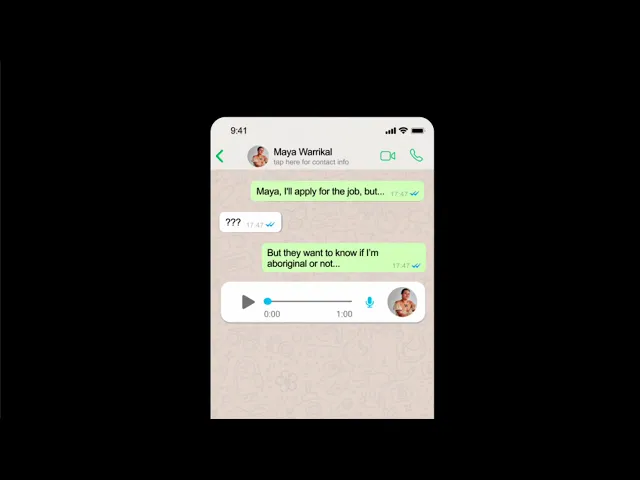

Digital hiring processes often include seemingly neutral steps identity declarations, background questions, eligibility checks that can carry disproportionate emotional weight for Aboriginal applicants. These small interactions can trigger hesitation, fear of discrimination, or a sense of vulnerability long before the interview even begins.

Imagine this: you’re an Aboriginal applicant in Australia, about to apply for a job. Before you can even show your skills, the hiring form asks you to declare your identity.

What feels like a routine question for most people suddenly becomes a moment loaded with doubt:

“Should I say it? Will it affect my chances? What if it changes how they see me?”

Digital hiring processes often include seemingly neutral steps identity declarations, background questions, eligibility checks that can carry disproportionate emotional weight for Aboriginal applicants. These small interactions can trigger hesitation, fear of discrimination, or a sense of vulnerability long before the interview even begins.

Imagine this: you’re an Aboriginal applicant in Australia, about to apply for a job. Before you can even show your skills, the hiring form asks you to declare your identity.

What feels like a routine question for most people suddenly becomes a moment loaded with doubt:

“Should I say it? Will it affect my chances? What if it changes how they see me?”

Digital hiring processes often include seemingly neutral steps identity declarations, background questions, eligibility checks that can carry disproportionate emotional weight for Aboriginal applicants. These small interactions can trigger hesitation, fear of discrimination, or a sense of vulnerability long before the interview even begins.

How might we turn a missing form into a story?

How might we turn a missing form into a story?

How might we turn a missing form into a story?

Laying the Groundwork

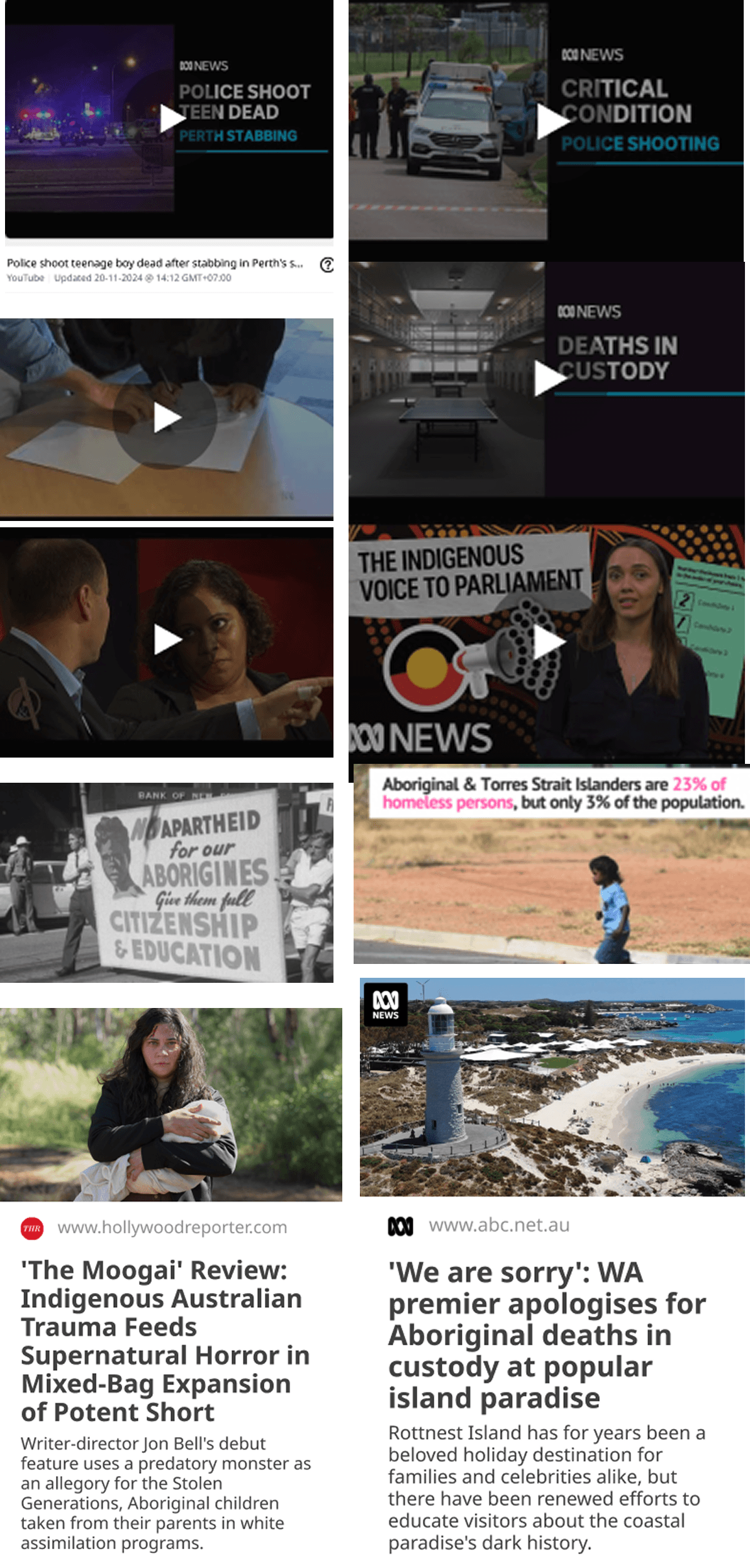

As part of a university assignment, we were asked to design a VR experience. I had no background in VR, but one project from earlier lectures stuck with me We Are Always Here from the VR for Good series. It showed how VR can quietly carry emotion through space, not explanation.

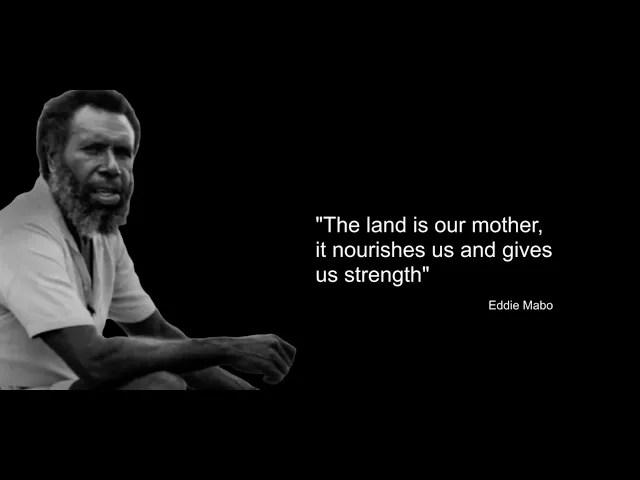

That idea stayed with me. I started reflecting on everyday interactions that carry invisible tension. The experience of filling in forms stood out especially the question about Aboriginal identity. I remembered conversations with a friend who is Aboriginal, and validated my assumptions with her to ground the concept in real experiences.

From there, I began shaping a space where the tension isn't told but felt.

Early Exploration

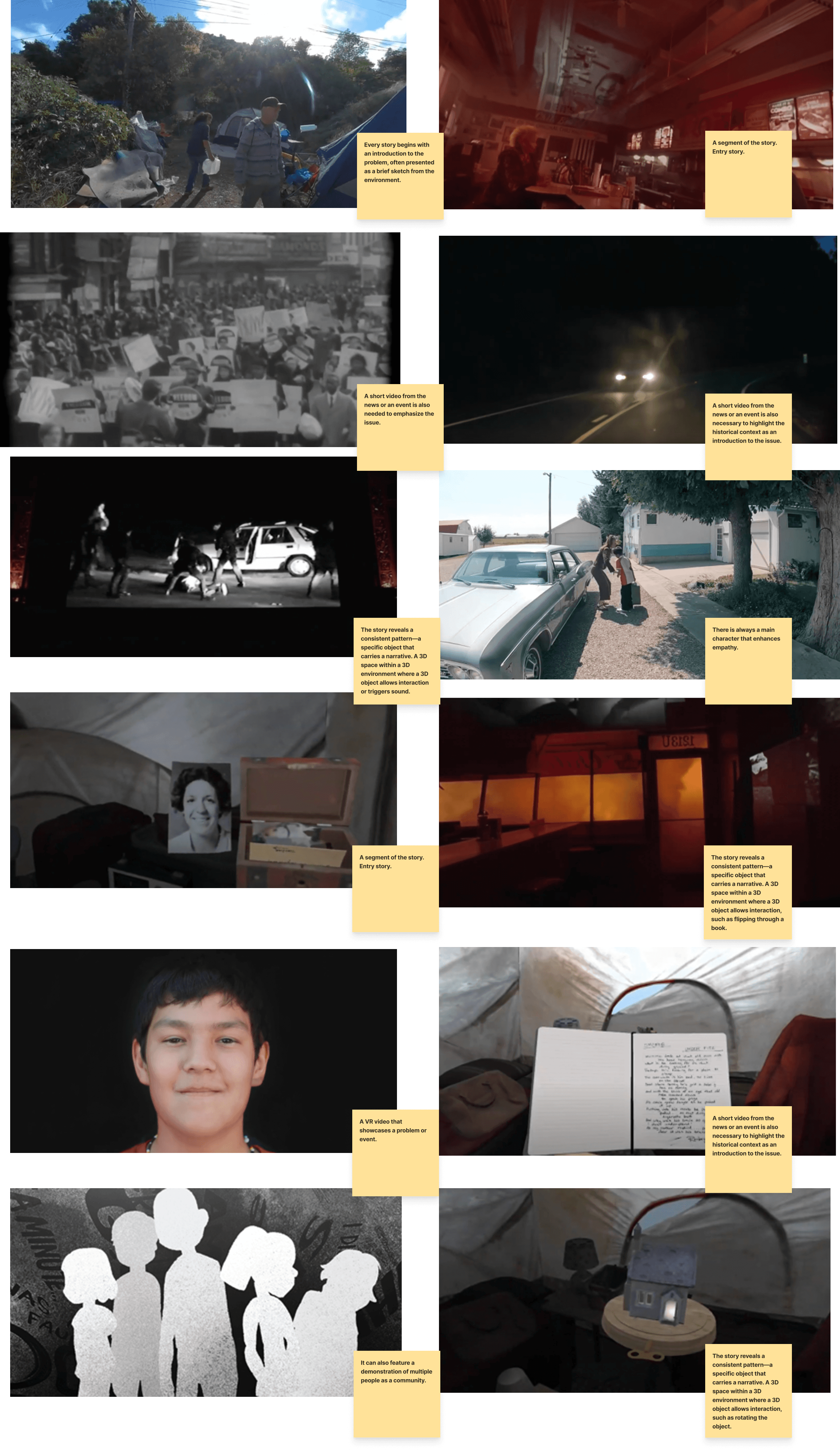

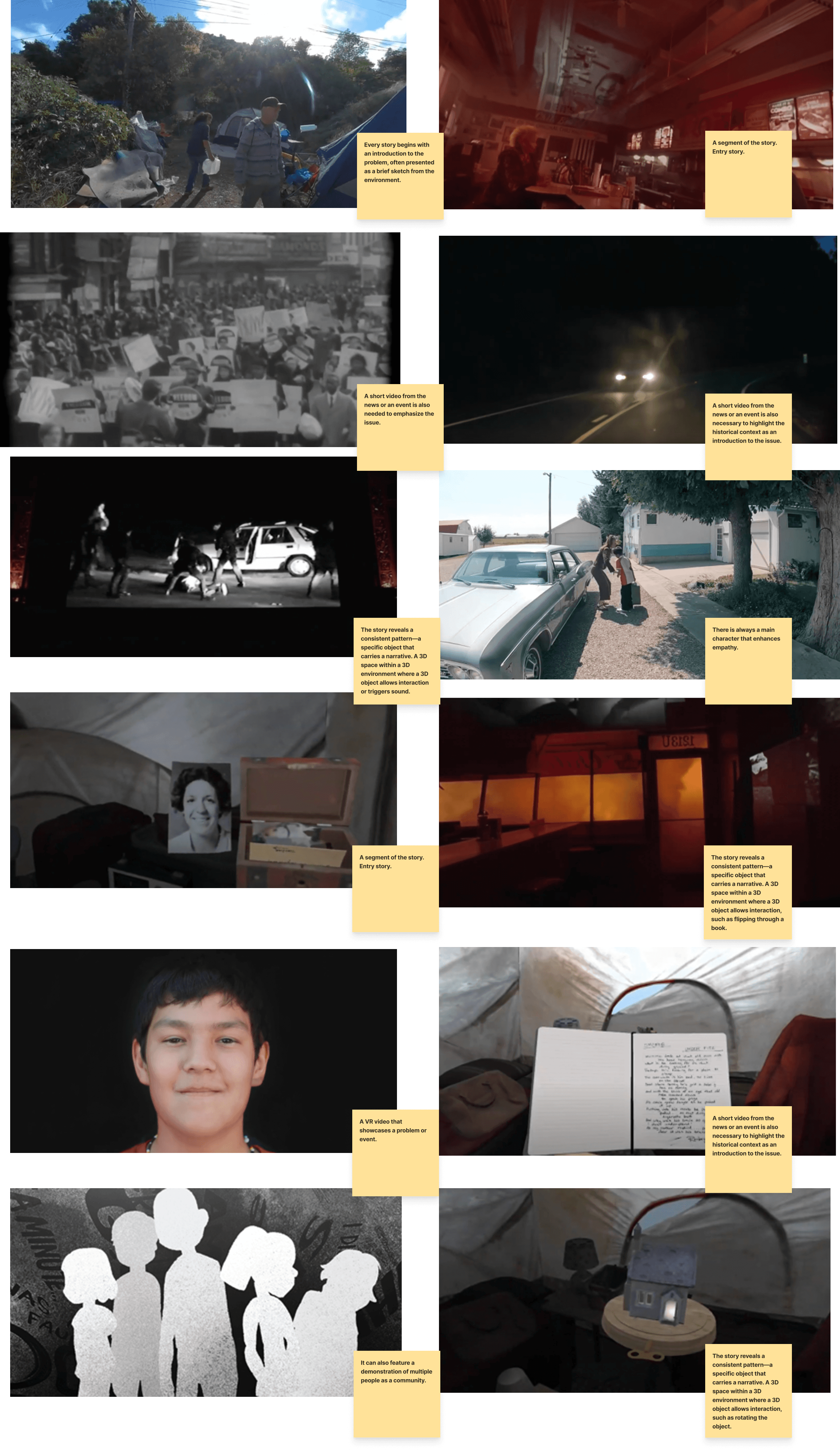

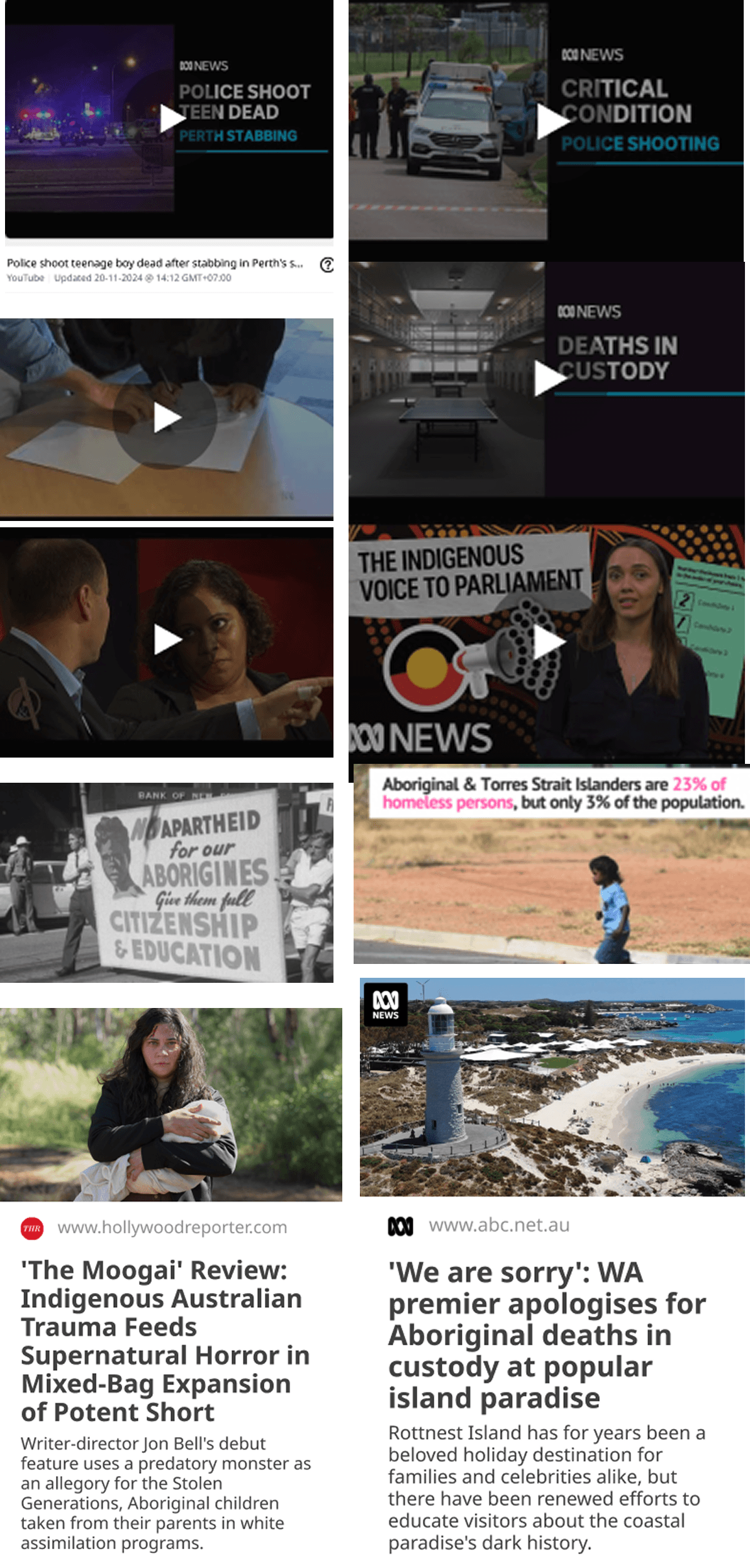

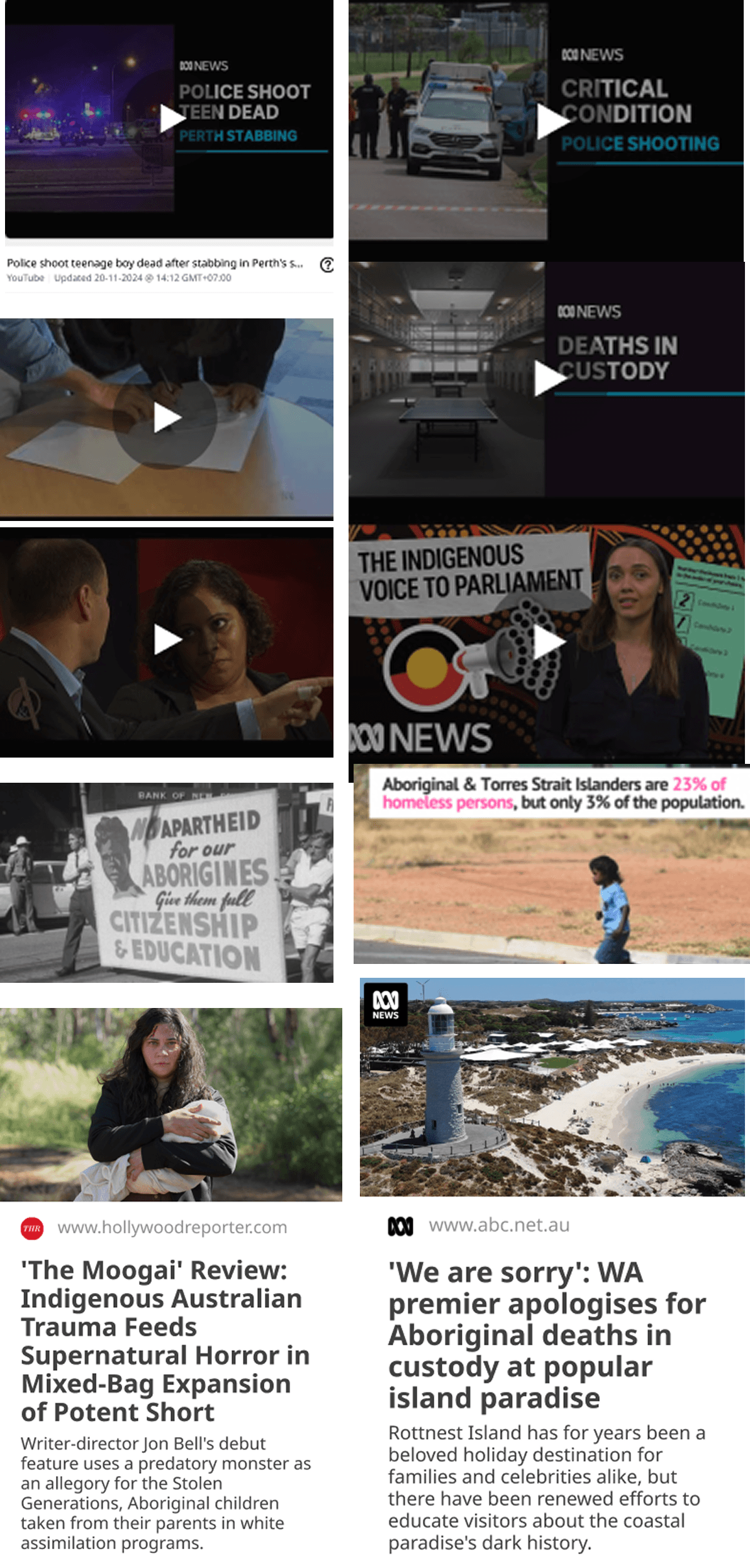

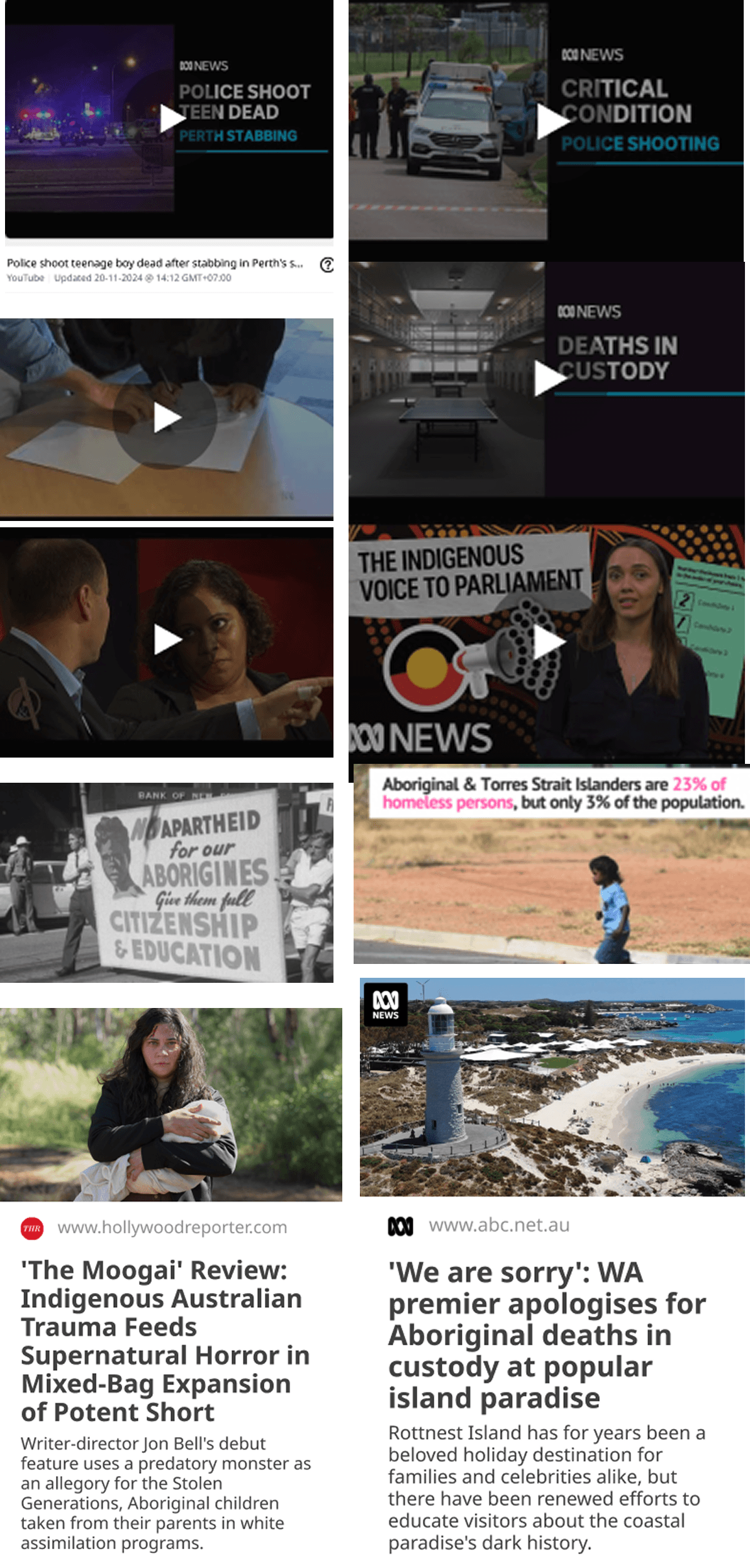

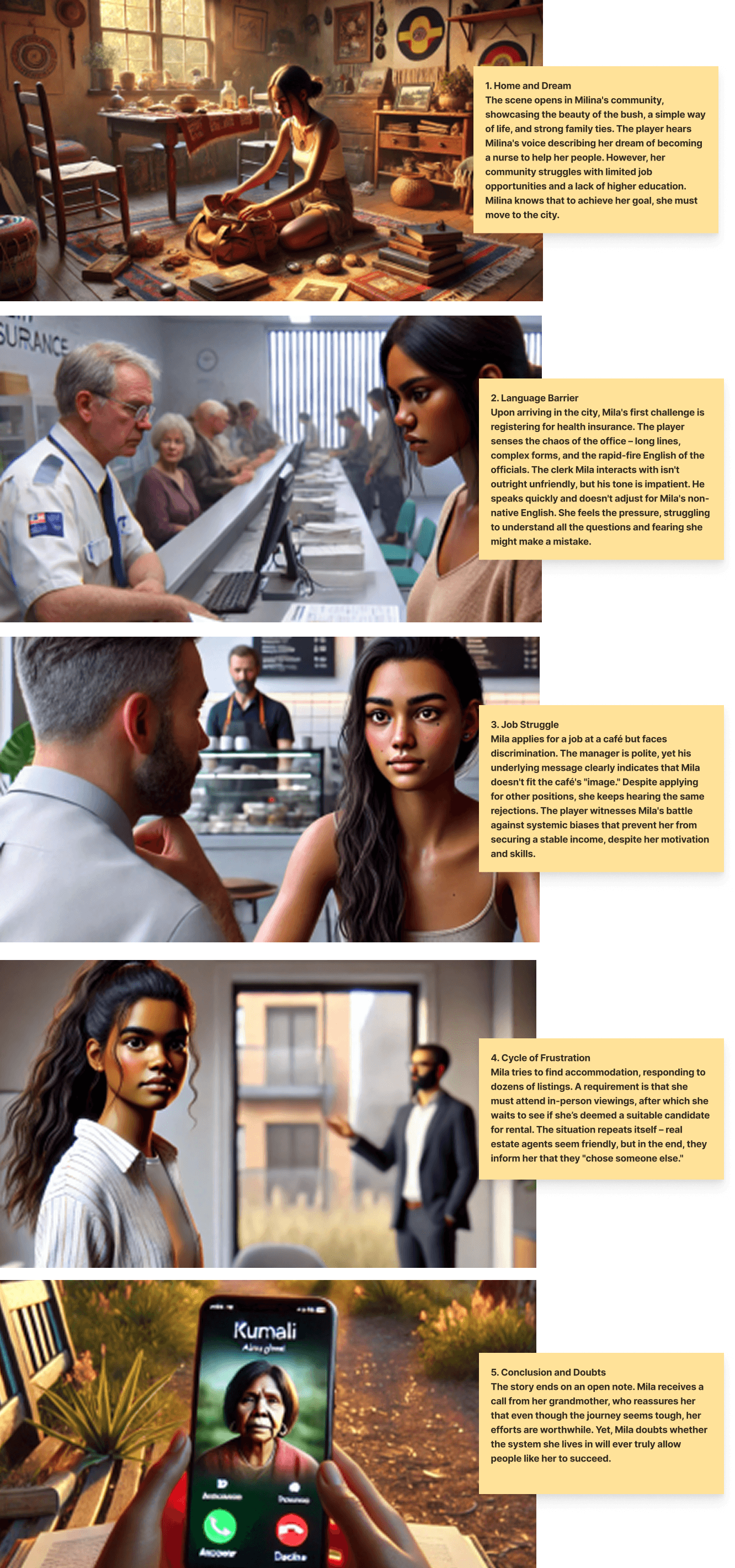

Once I gathered context and real input, I started visual exploration. I created a moodboard to map possible scenes and tones including public offices, schools, police interactions, and job interviews.

I wasn’t looking for drama, but for spaces where systems quietly create pressure. The job interview scene stood out: it’s familiar, controlled, and filled with unspoken rules.

From there, I began sketching how the space could “talk” not through voice, but through cues like awkward silences, alerts on screen, or subtle tension in posture. The idea wasn’t to recreate a conversation, but to let users feel the weight of it without words.

Brainstorming

Articles

AI ideas

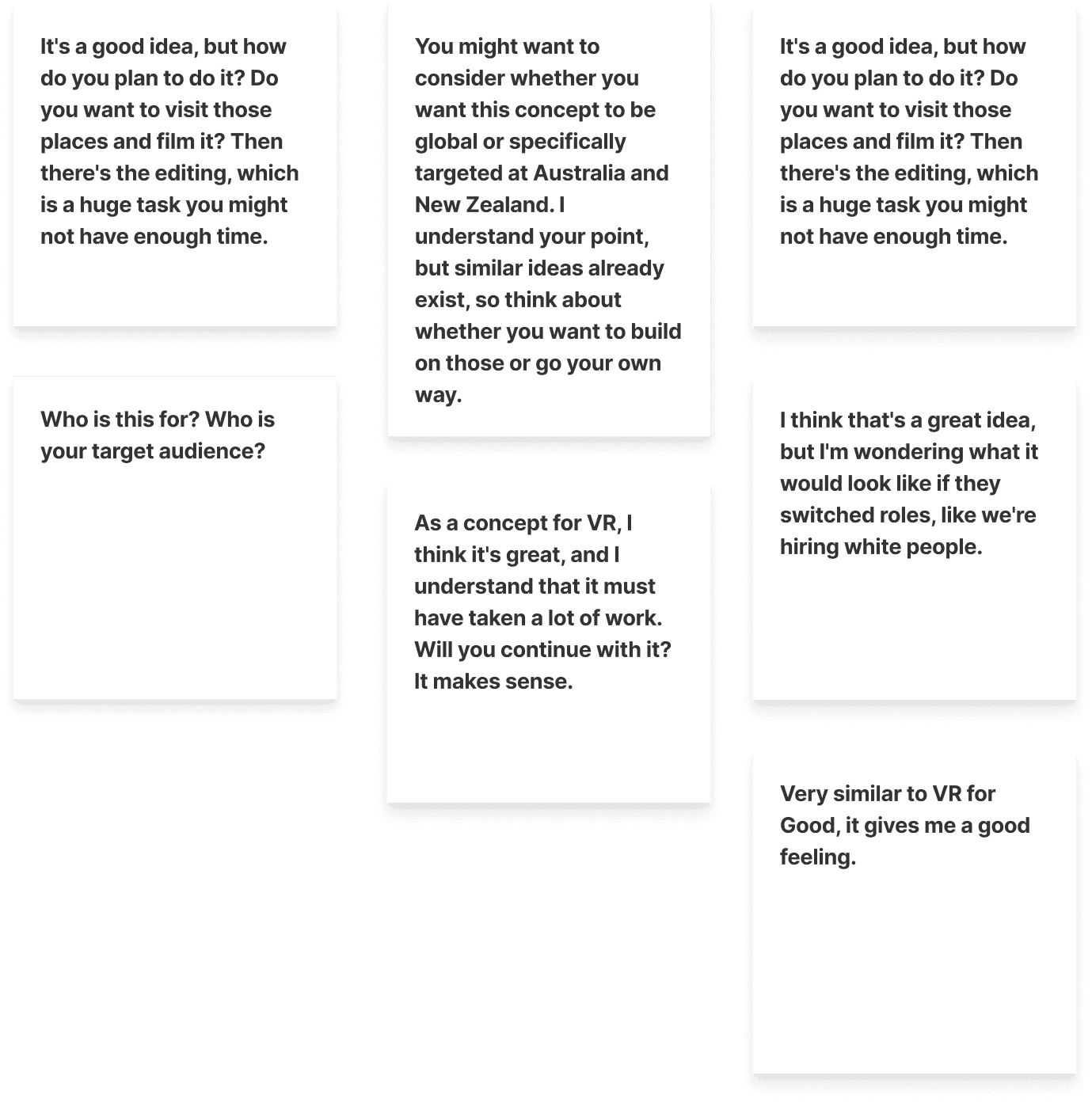

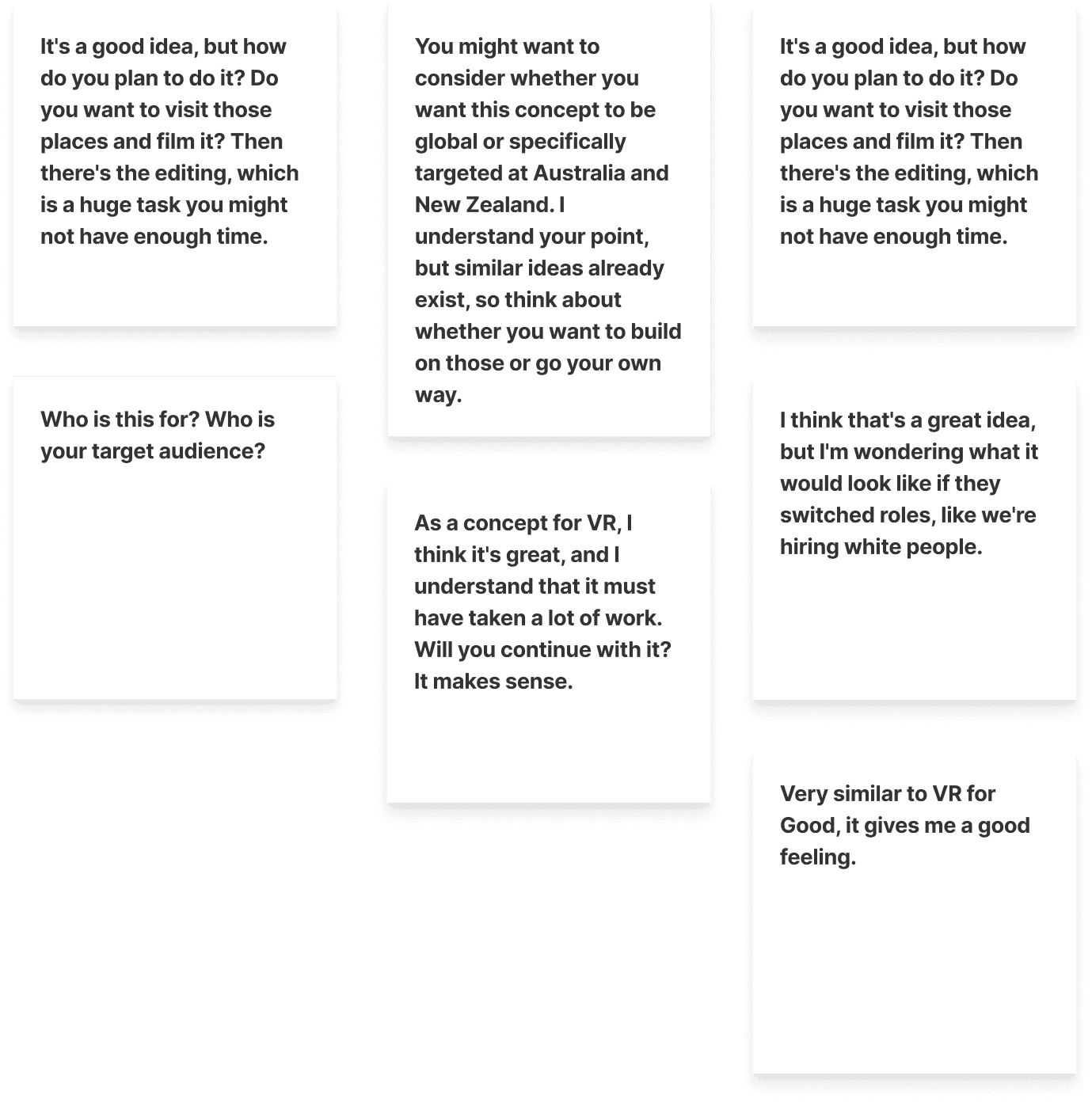

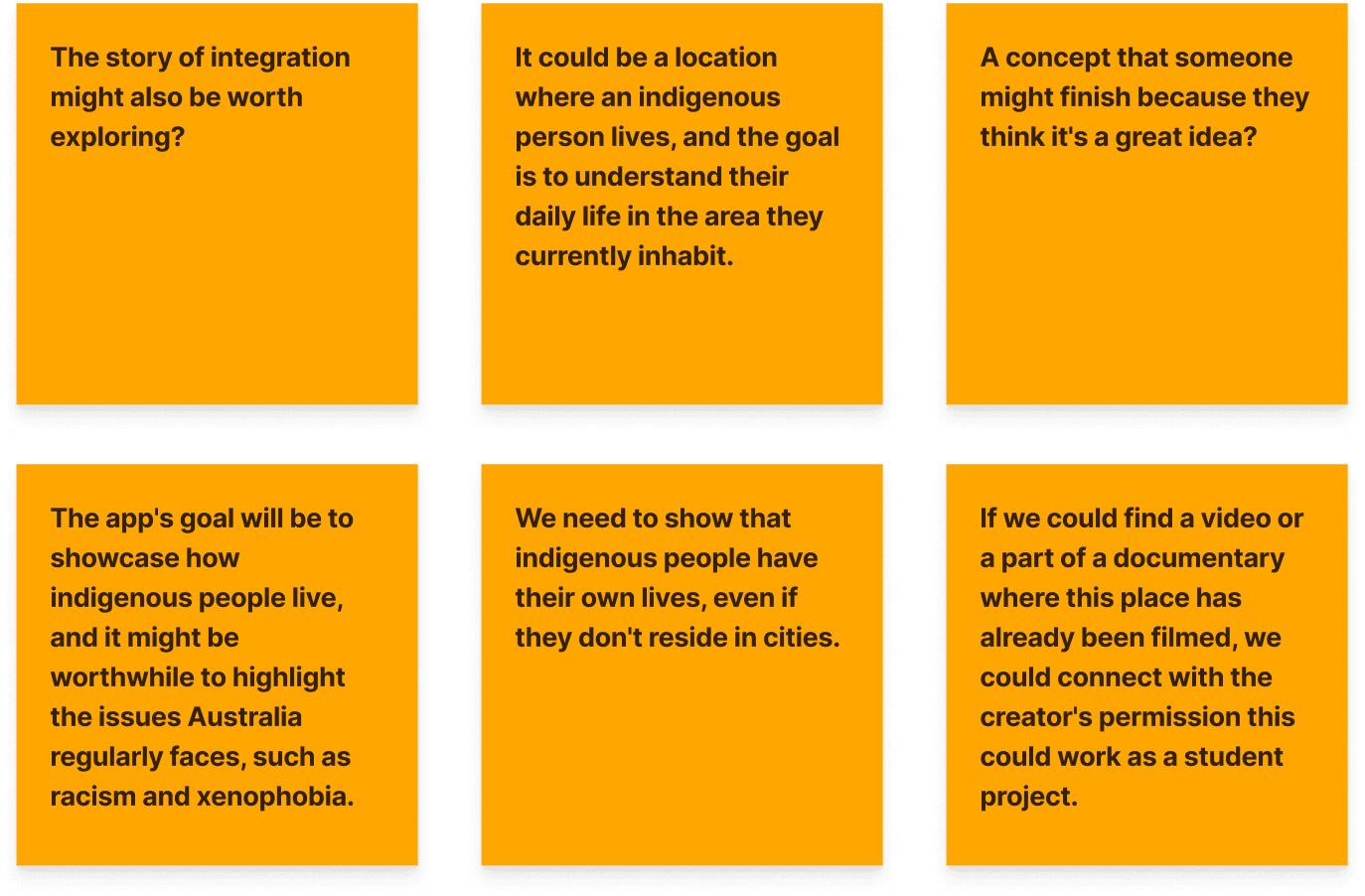

Eearly feedback

Demonstration of ideas

Strangers

at home

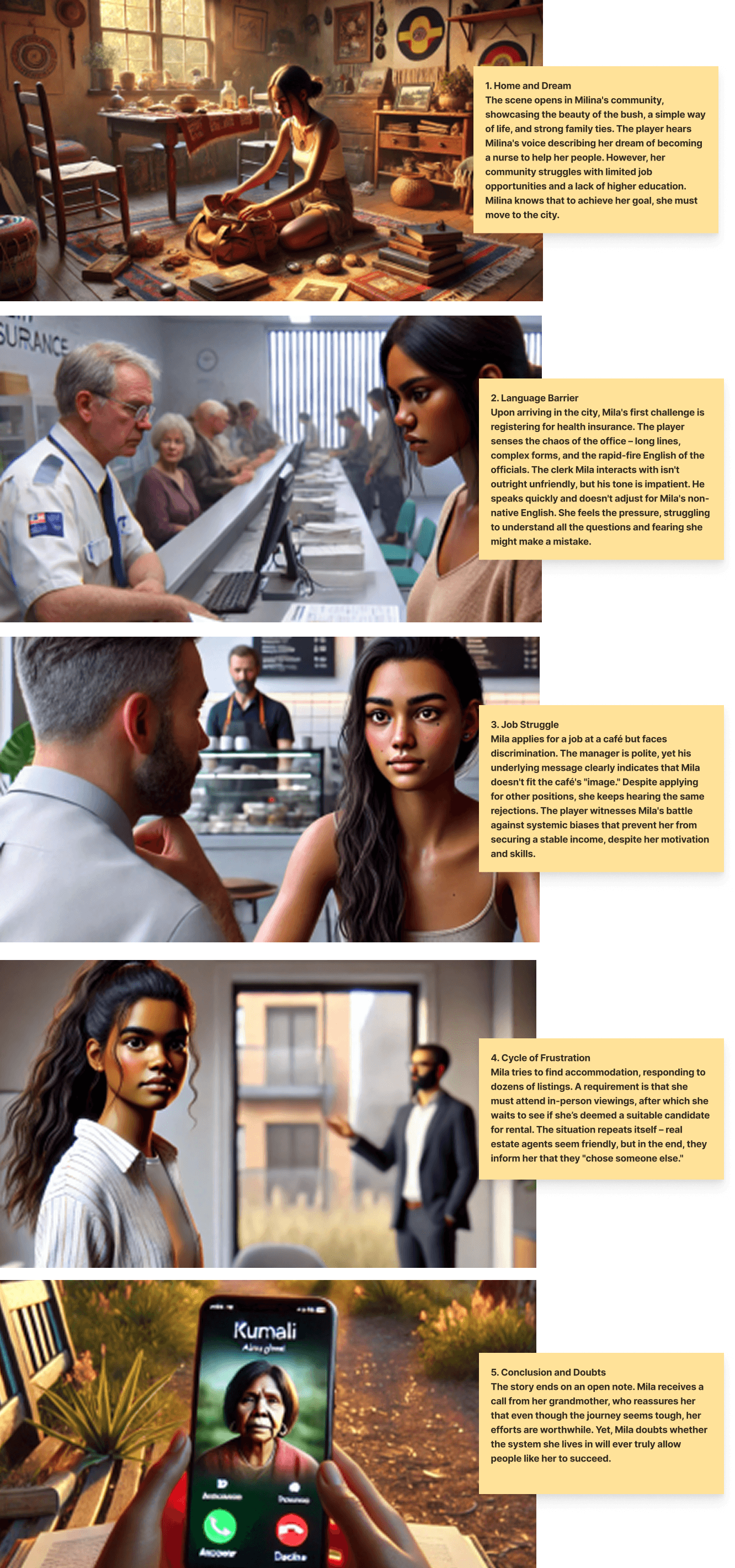

Strangers at Home is a VR concept exploring how everyday interactions can create unequal experiences for Indigenous job applicants in Australia.

Category:

VR concept, VR for good

Client:

Masaryk University

Duration:

7 weeks

Location:

Perth, Western Australia

Tools:

Miro, Figma, Adobe Premiere,

Youtube, Gemini, Shapes XR

Strangers

at home

Strangers at Home is a VR concept exploring how everyday interactions can create unequal experiences for Indigenous job applicants in Australia.

Category:

VR concept, VR for good

Client:

Masaryk University

Duration:

7 weeks

Location:

Perth, Western Australia

Tools:

Miro, Figma, Adobe Premiere, Youtube, Gemini, Shapes XR

Strangers

at home

Strangers at Home is a VR concept exploring how everyday interactions can create unequal experiences for Indigenous job applicants in Australia.

Category:

VR concept, VR for good

Client:

Masaryk University

Duration:

7 weeks

Location:

Perth, Western Australia

Tools:

Miro, Figma, Adobe Premiere, Youtube, Gemini, Shapes XR

Laying the Groundwork

As part of a university assignment, we were asked to design a VR experience. I had no background in VR, but one project from earlier lectures stuck with me We Are Always Here from the VR for Good series. It showed how VR can quietly carry emotion through space, not explanation.

That idea stayed with me. I started reflecting on everyday interactions that carry invisible tension. The experience of filling in forms stood out especially the question about Aboriginal identity. I remembered conversations with a friend who is Aboriginal, and validated my assumptions with her to ground the concept in real experiences.

From there, I began shaping a space where the tension isn't told but felt.

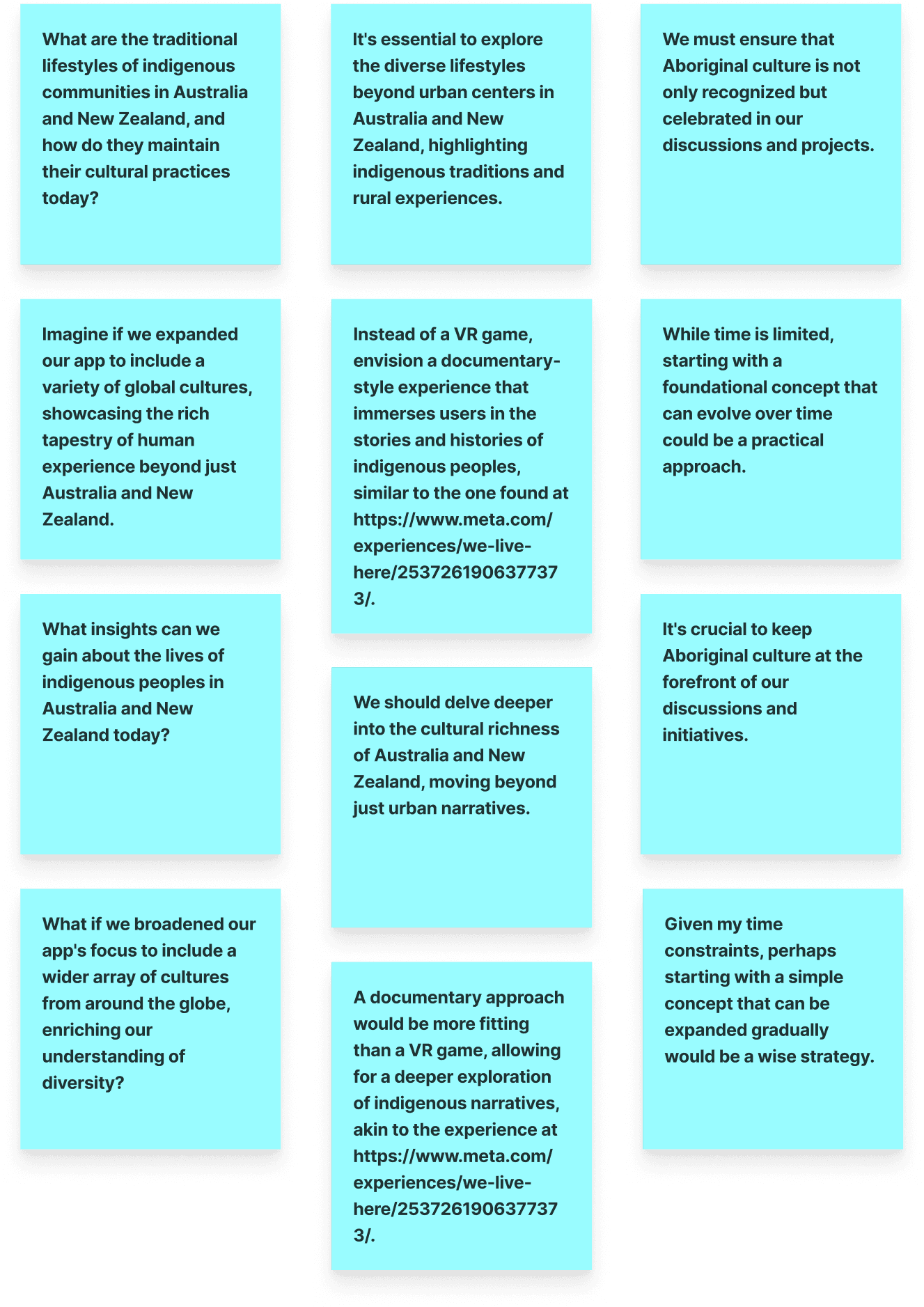

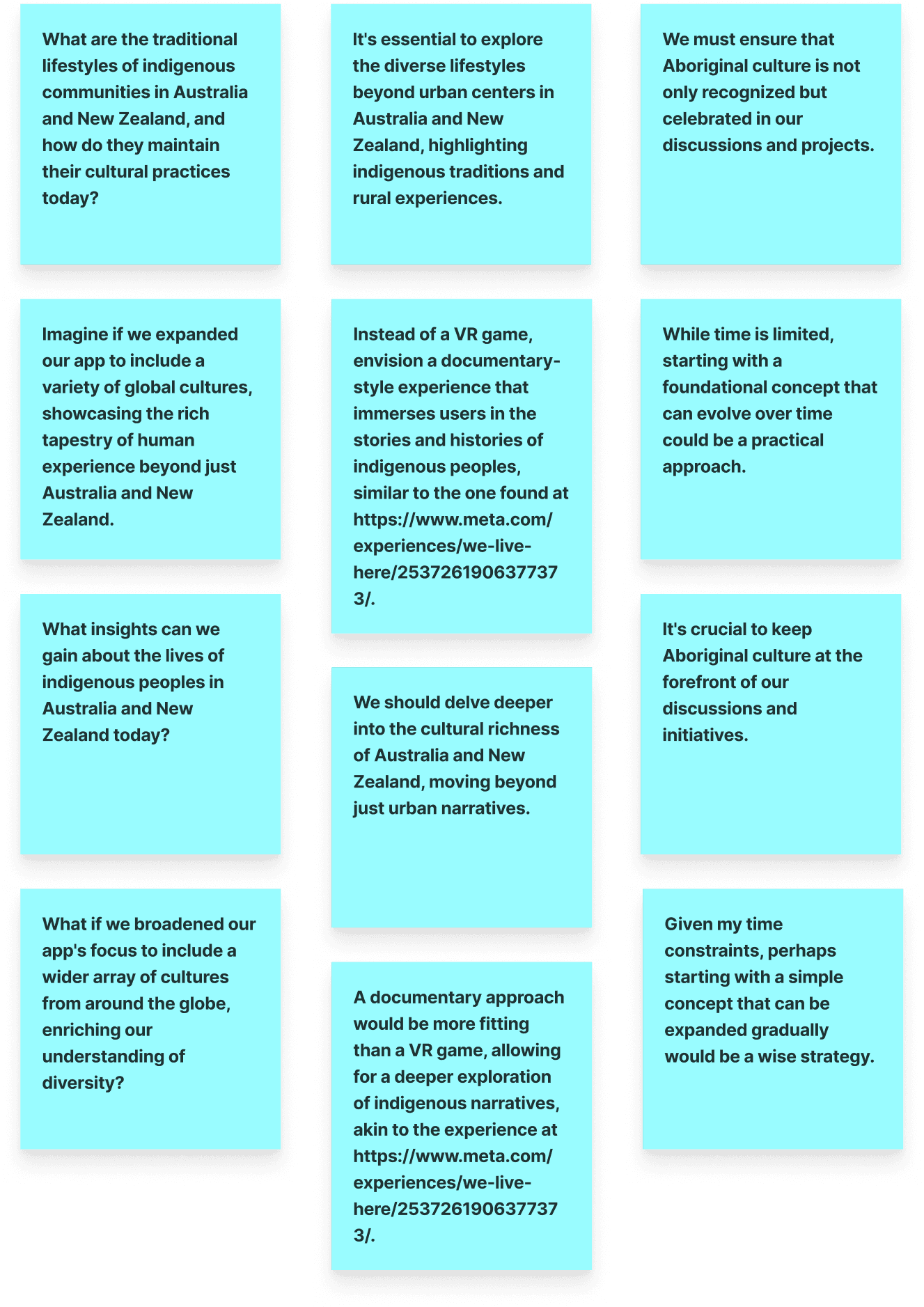

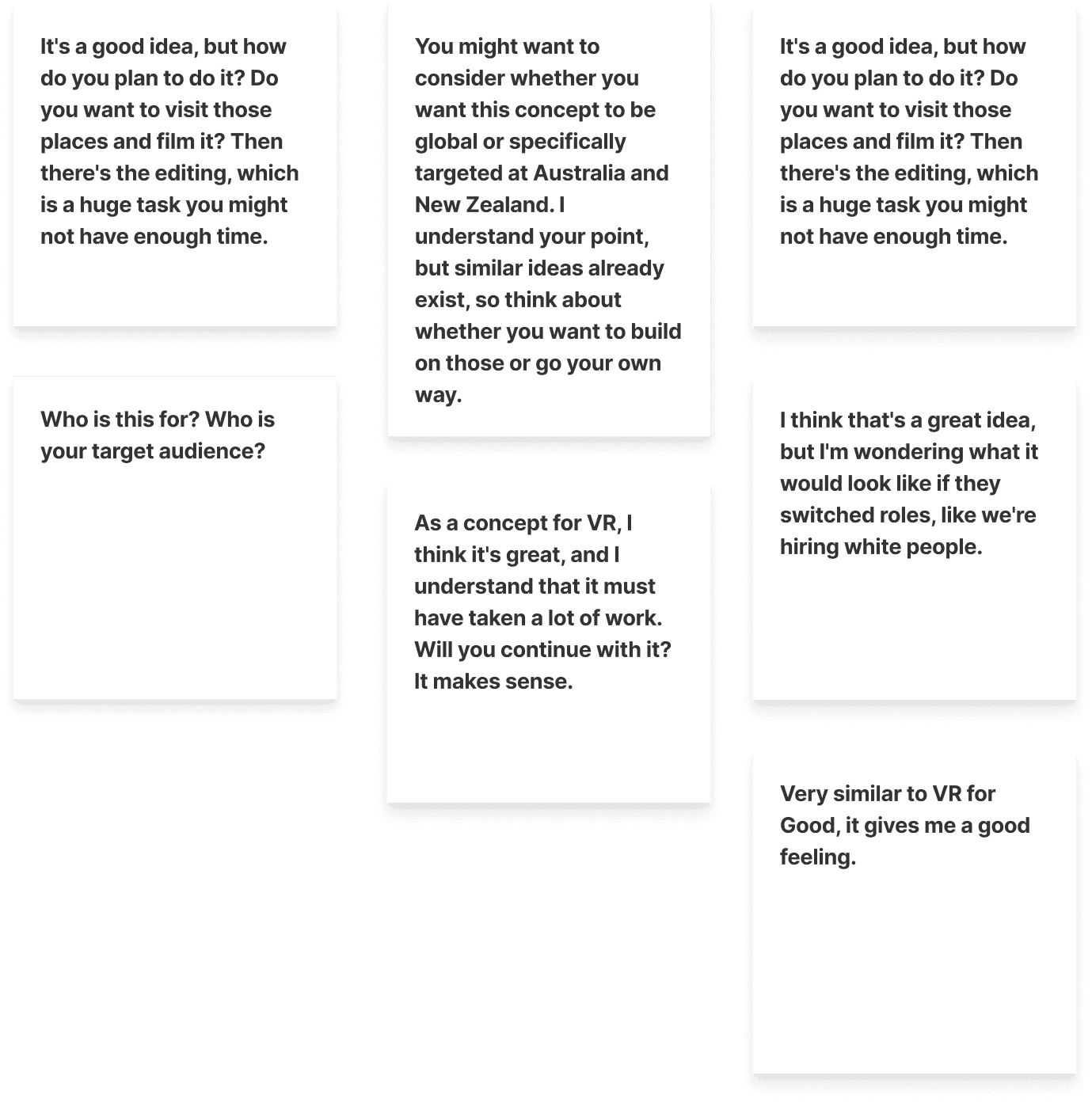

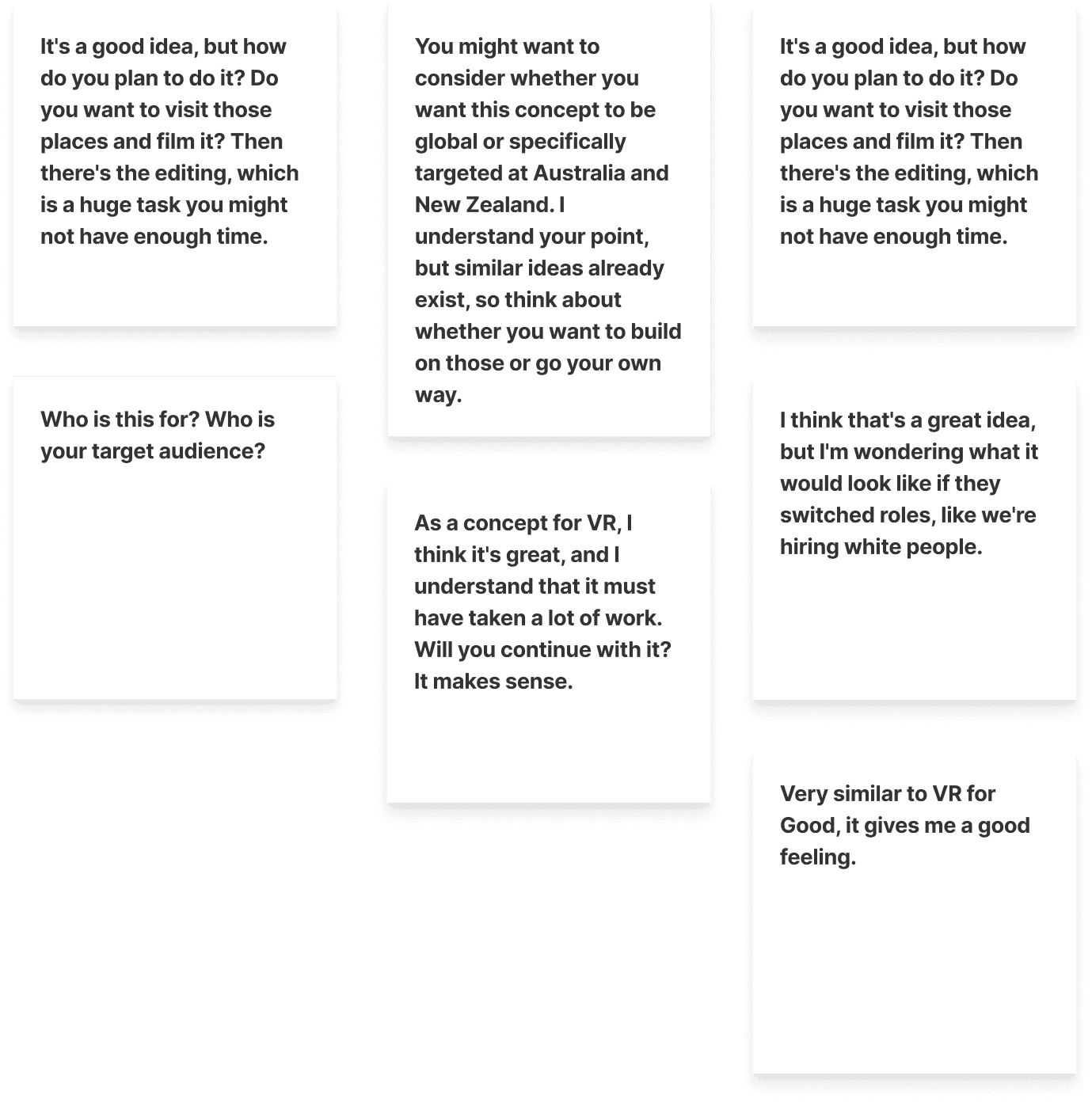

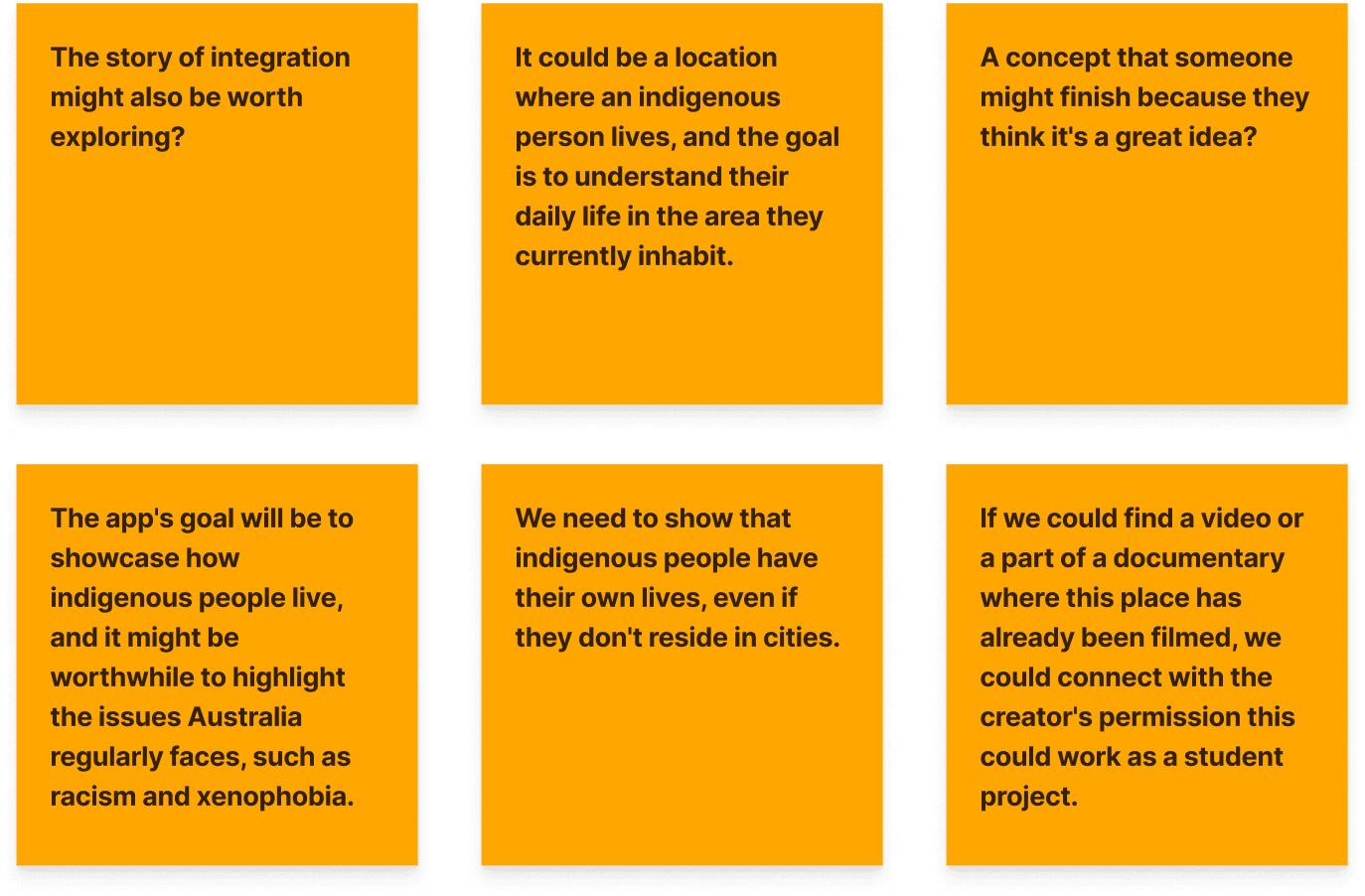

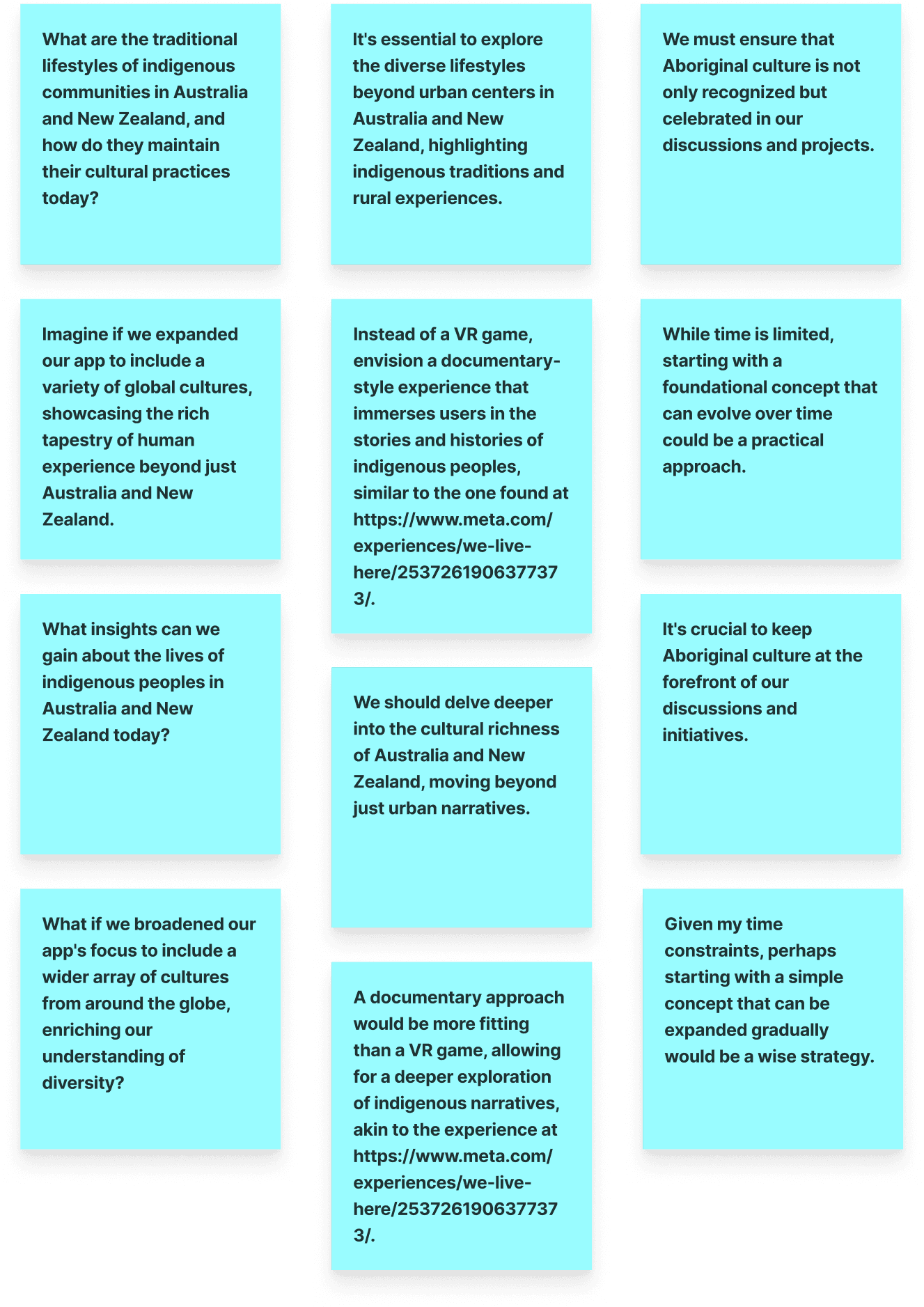

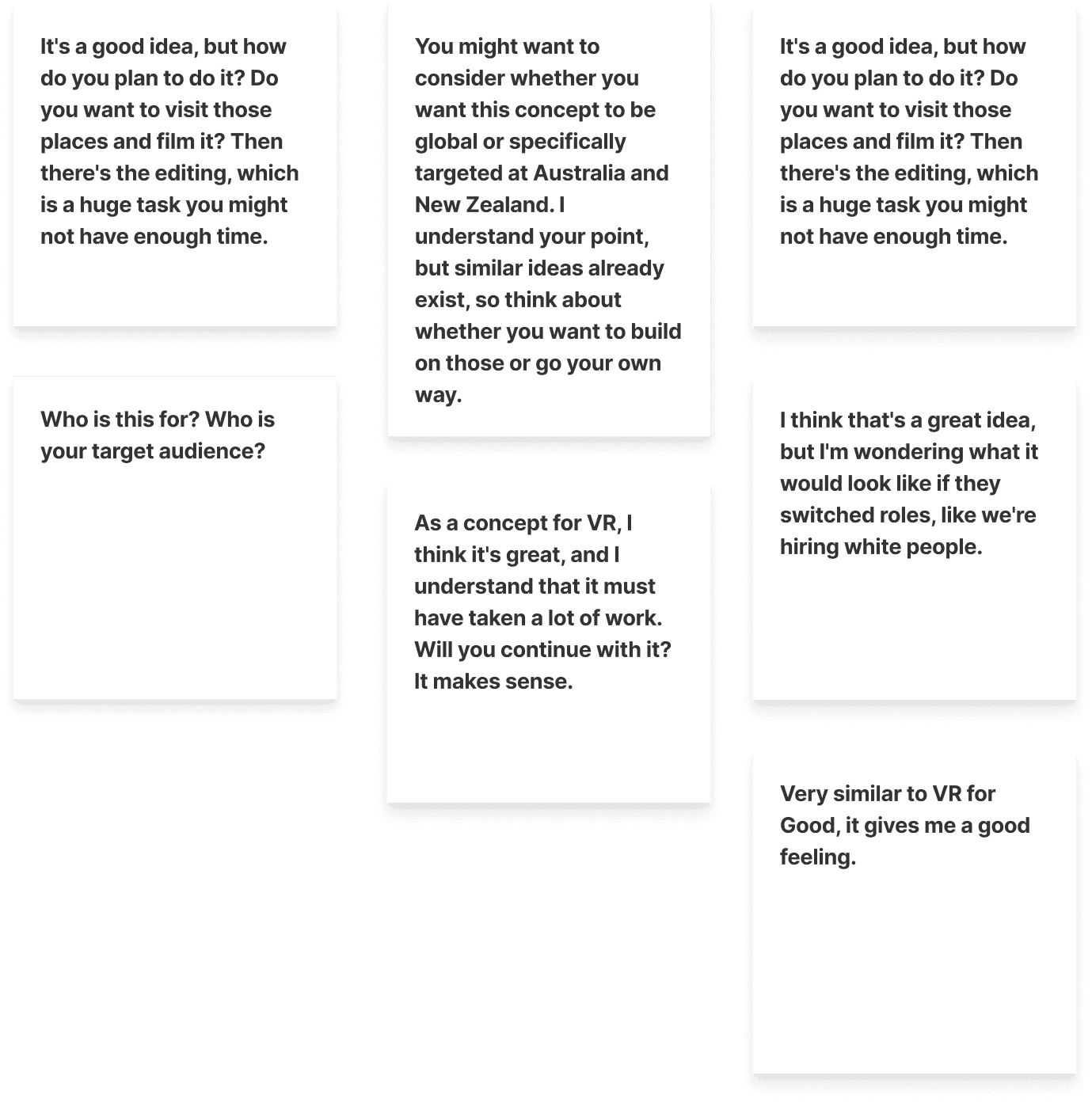

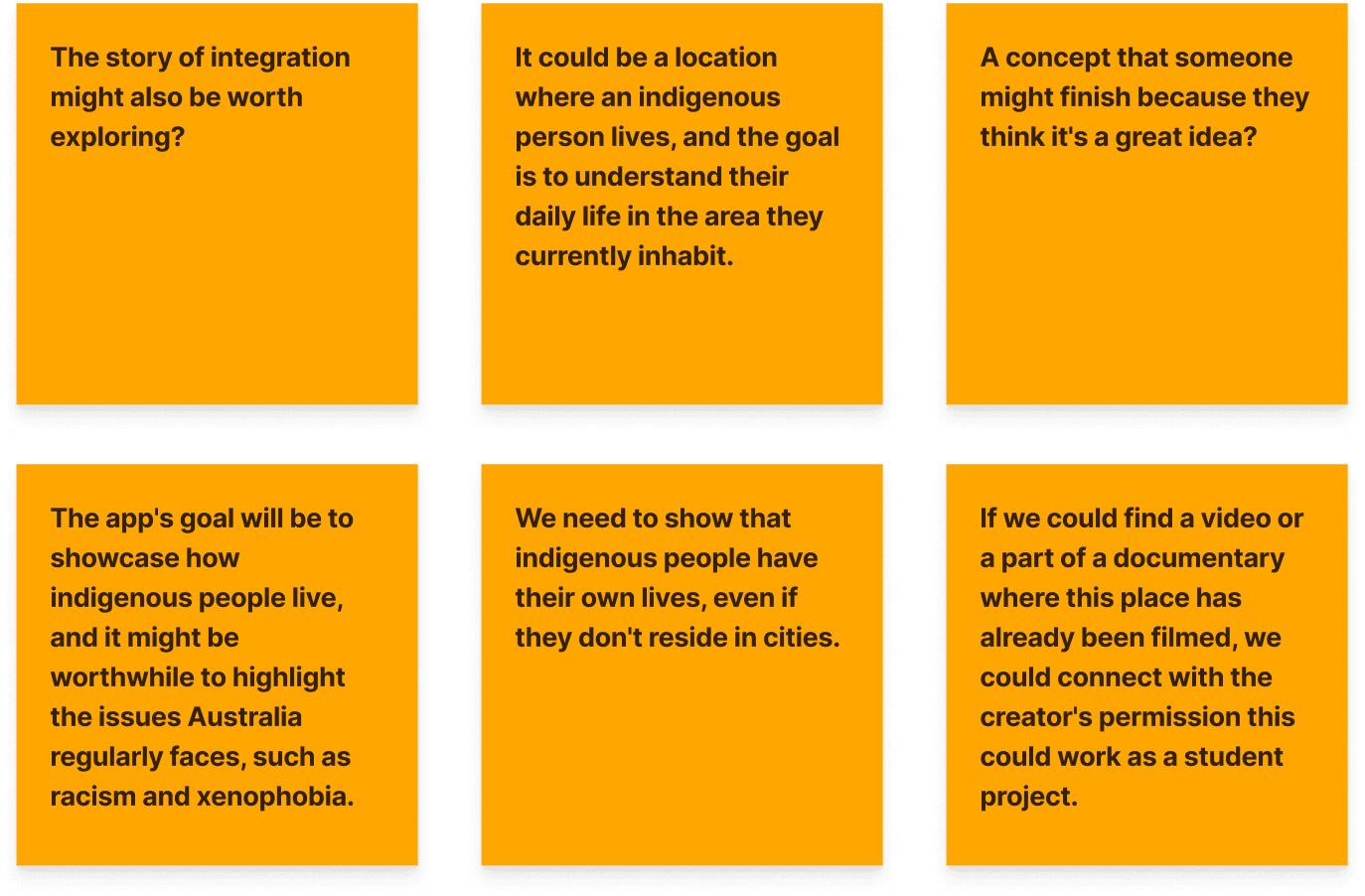

Brainstorming

Articles

AI ideas

Eearly feedback

Demonstration of ideas

Laying the Groundwork

As part of a university assignment, we were asked to design a VR experience. I had no background in VR, but one project from earlier lectures stuck with me We Are Always Here from the VR for Good series. It showed how VR can quietly carry emotion through space, not explanation.

That idea stayed with me. I started reflecting on everyday interactions that carry invisible tension. The experience of filling in forms stood out especially the question about Aboriginal identity. I remembered conversations with a friend who is Aboriginal, and validated my assumptions with her to ground the concept in real experiences.

From there, I began shaping a space where the tension isn't told but felt.

Brainstorming

Articles

AI ideas

Eearly feedback

Demonstration of ideas

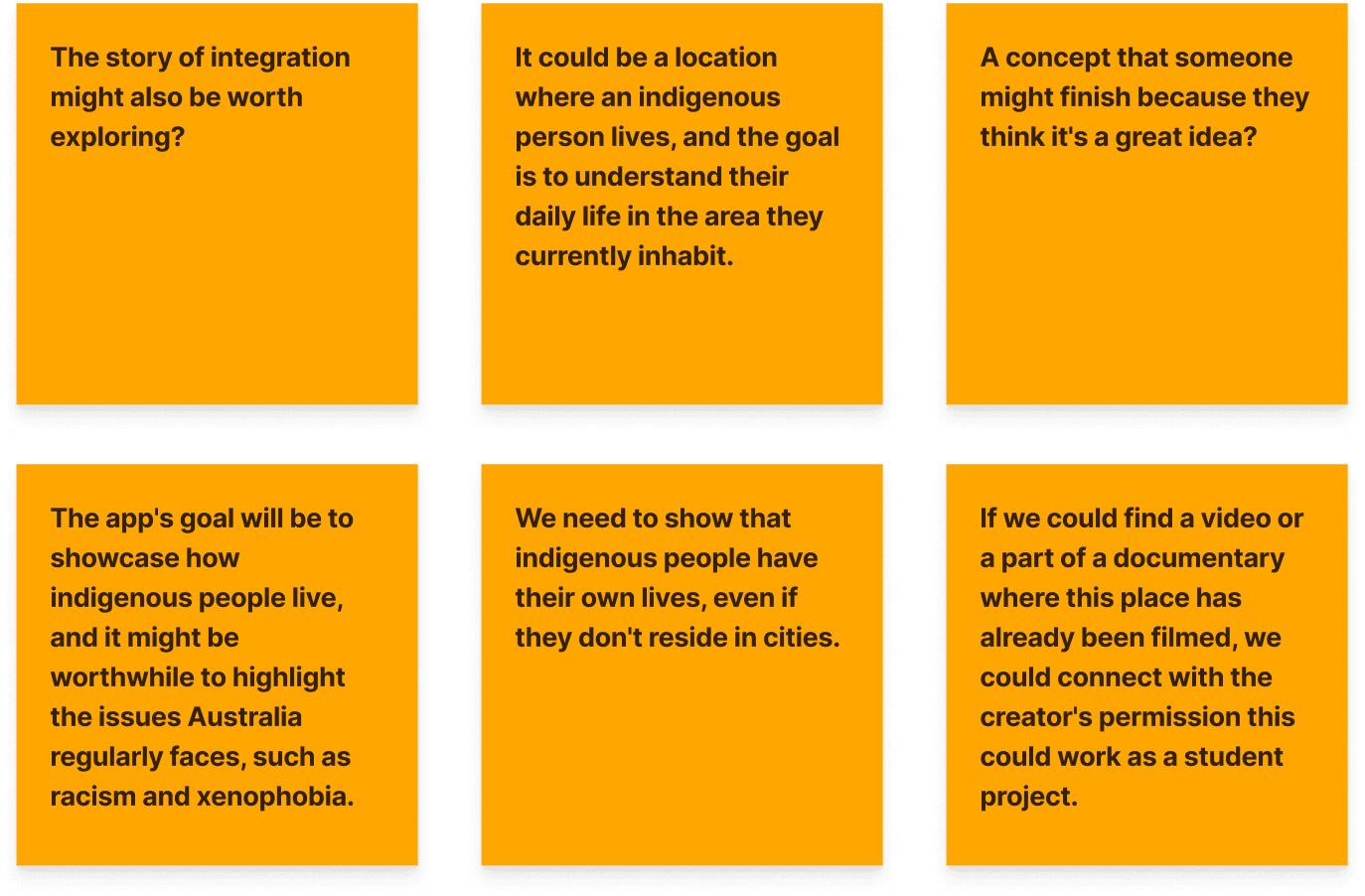

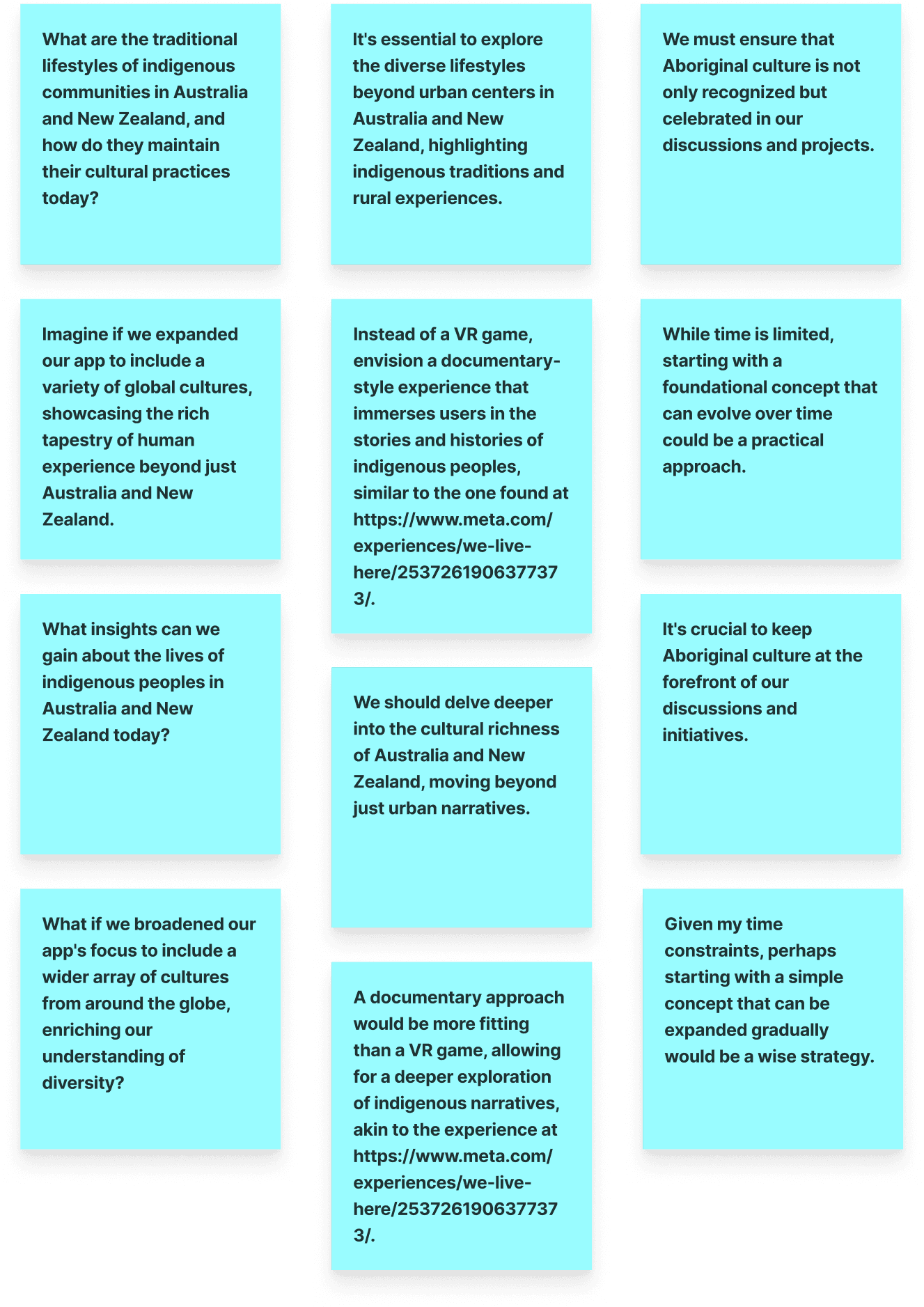

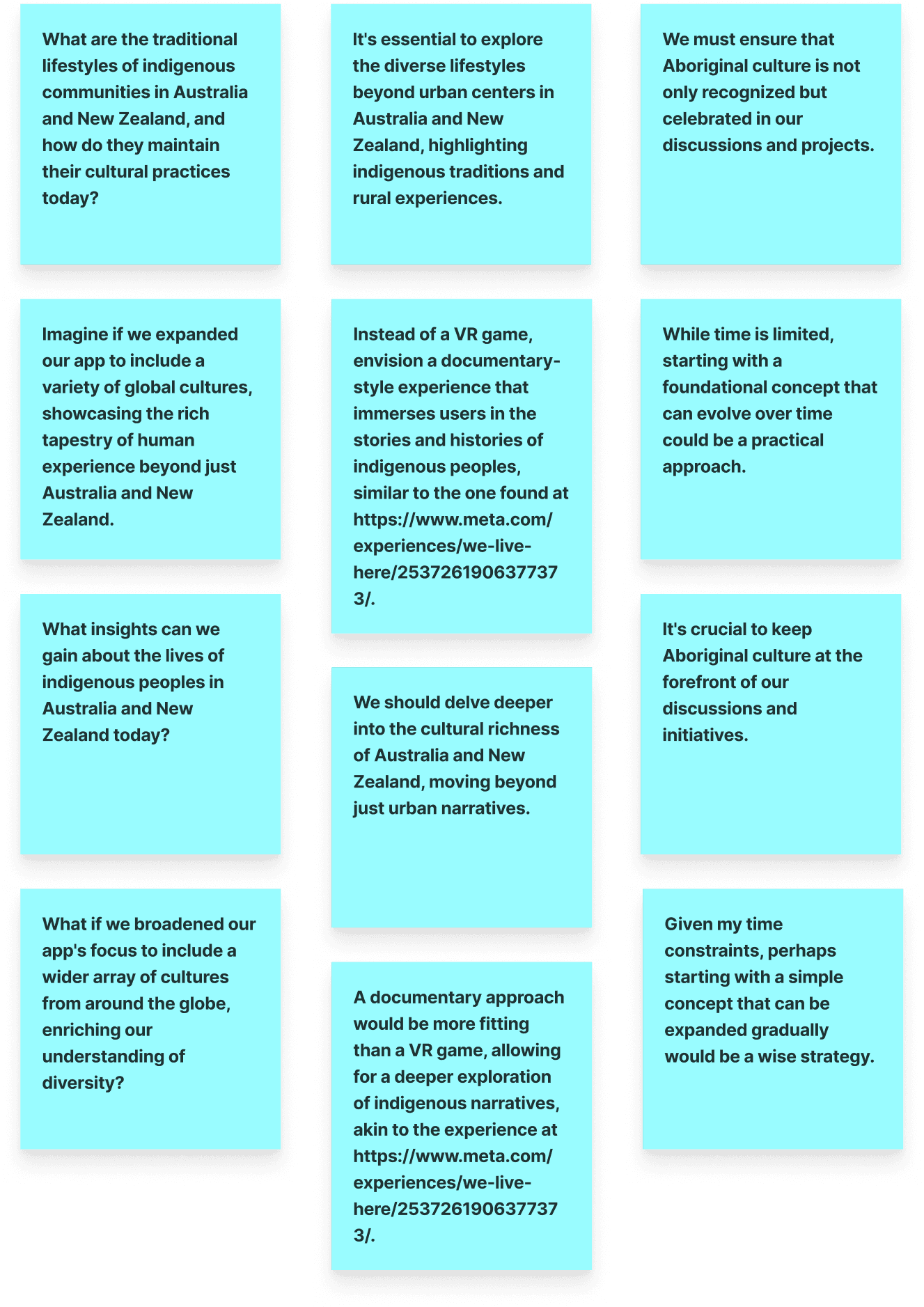

Inspiration

Narative research

Scene selections

Early Exploration

Once I gathered context and real input, I started visual exploration. I created a moodboard to map possible scenes and tones including public offices, schools, police interactions, and job interviews.

I wasn’t looking for drama, but for spaces where systems quietly create pressure. The job interview scene stood out: it’s familiar, controlled, and filled with unspoken rules.

From there, I began sketching how the space could “talk” not through voice, but through cues like awkward silences, alerts on screen, or subtle tension in posture. The idea wasn’t to recreate a conversation, but to let users feel the weight of it without words.

Early Exploration

Once I gathered context and real input, I started visual exploration. I created a moodboard to map possible scenes and tones including public offices, schools, police interactions, and job interviews.

I wasn’t looking for drama, but for spaces where systems quietly create pressure. The job interview scene stood out: it’s familiar, controlled, and filled with unspoken rules.

From there, I began sketching how the space could “talk” not through voice, but through cues like awkward silences, alerts on screen, or subtle tension in posture. The idea wasn’t to recreate a conversation, but to let users feel the weight of it without words.

Inspiration

Narative research

Scene selections

Prototyping

in virtual space

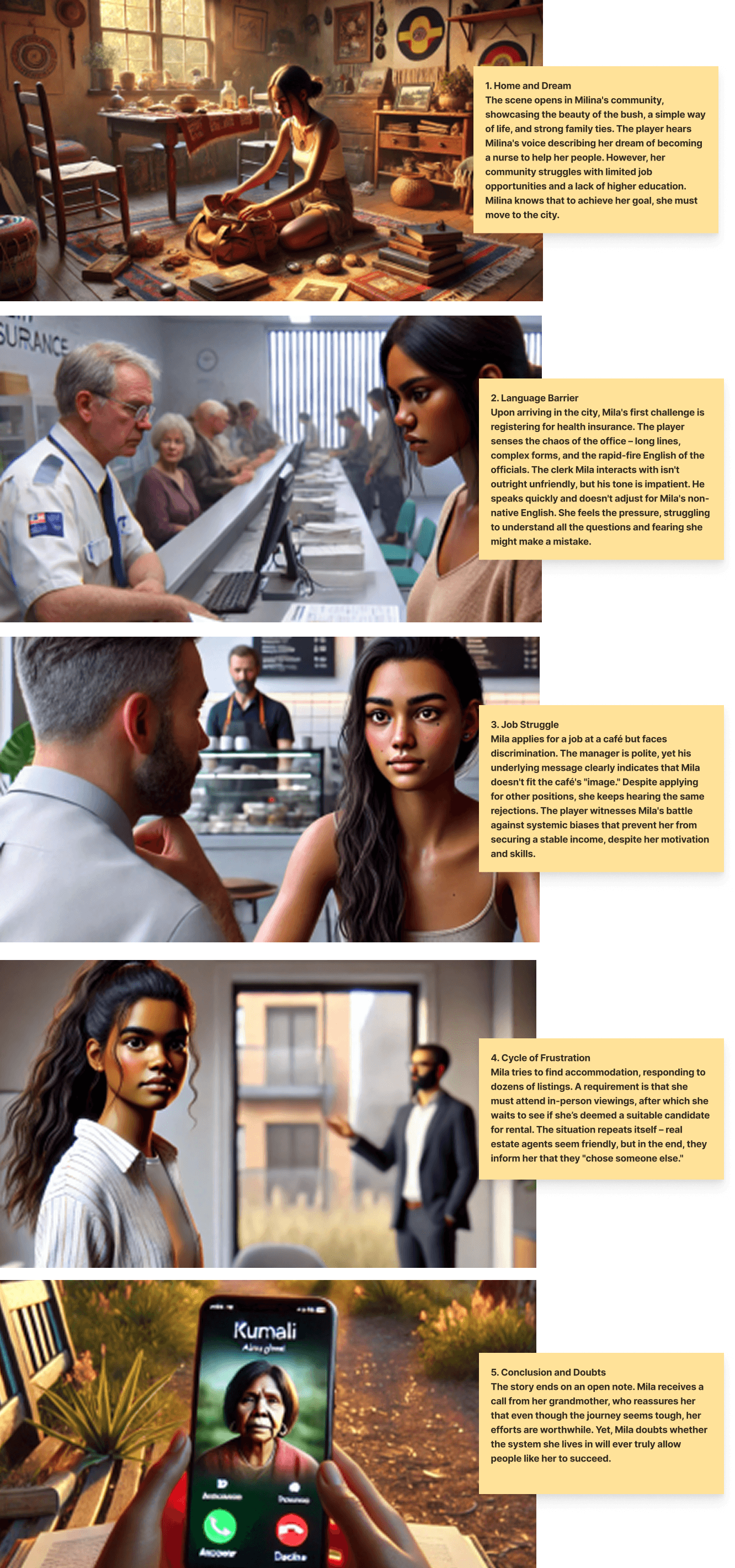

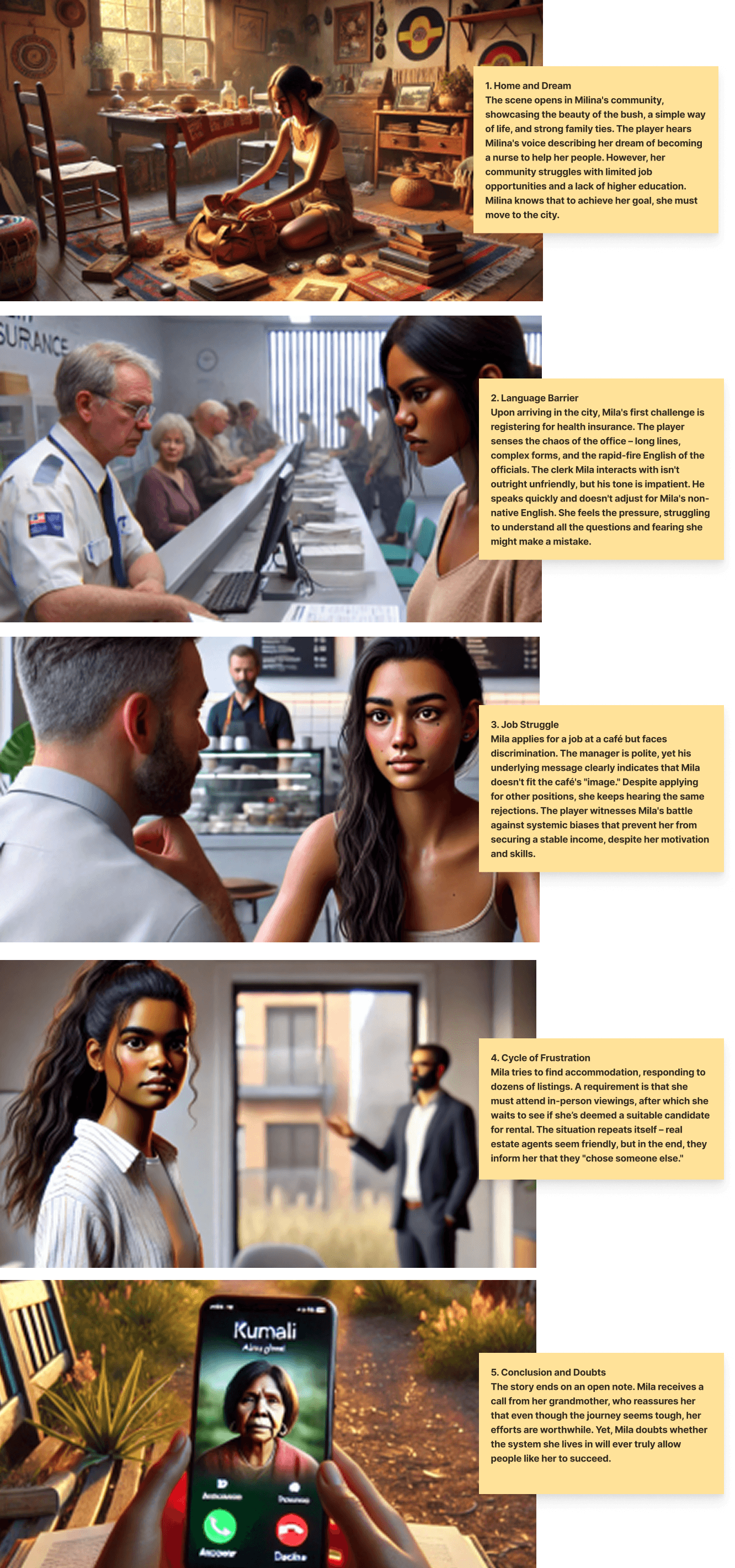

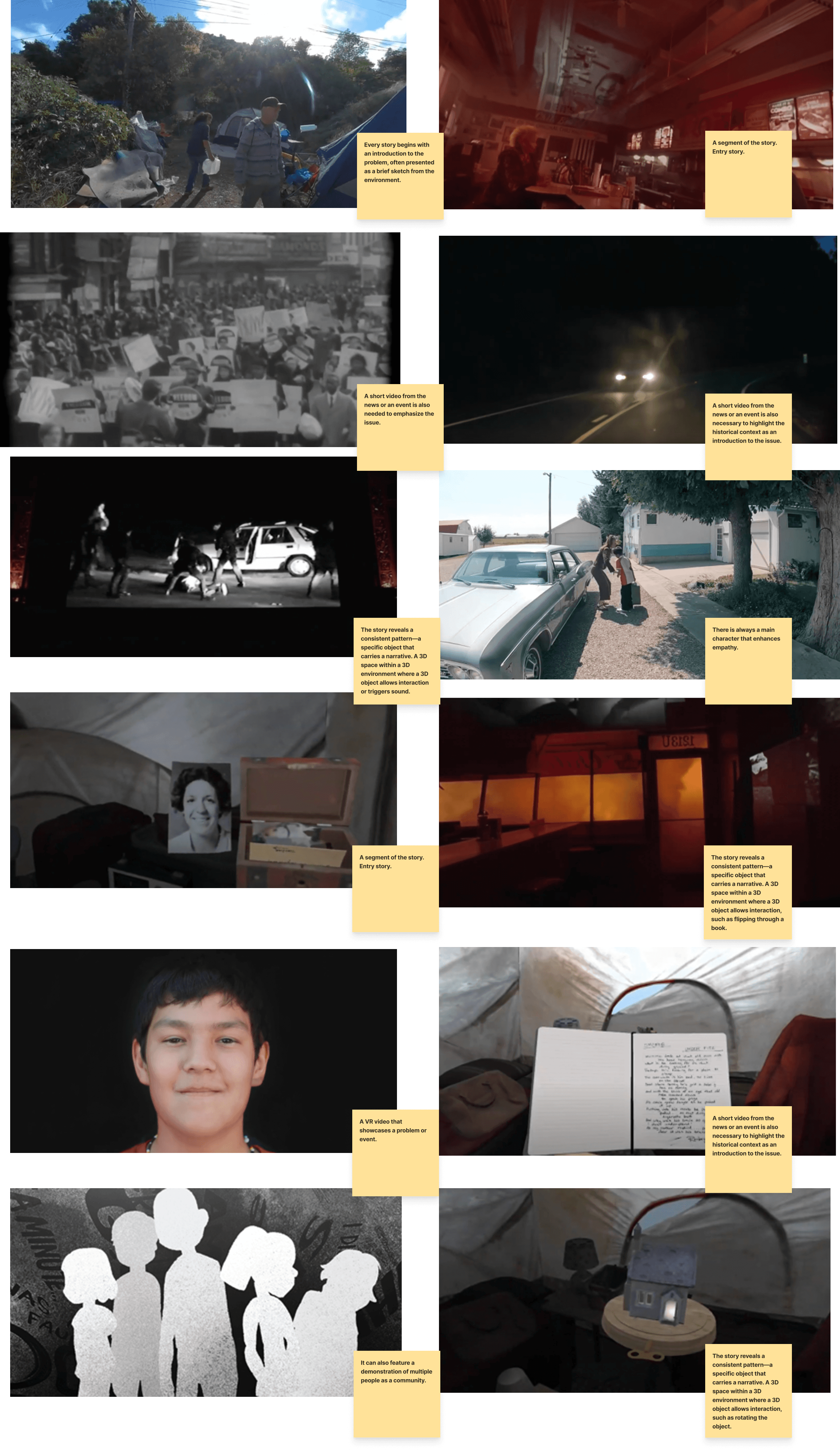

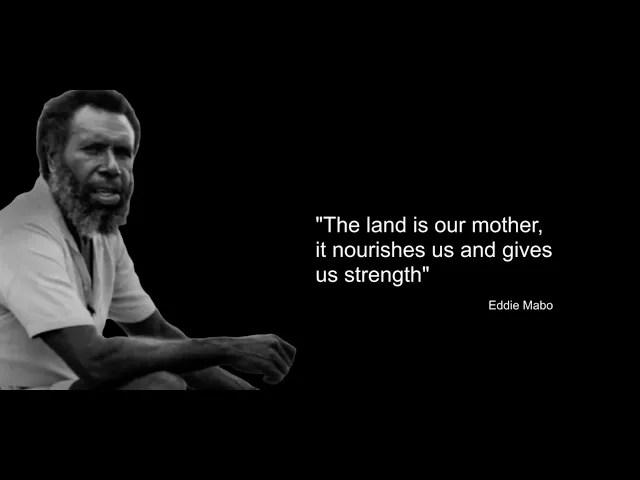

I wanted to follow the spirit of We Are Live Here, with no dialogues and a space that communicates through its environment. I began by building a simple test scene in ShapesXR to understand how elements behave in space, how different interactions feel such as clicking or gaze, and what naturally draws or shifts attention. ShapesXR let me quickly test layouts and interaction flows without focusing on visual fidelity.

I explored several scene ideas, but the job interview stood out as structured, familiar, and full of unspoken expectations. I designed the space so the user uncovers key moments gradually. A note on the desk. A voice message. A fragment of conversation. An alert on the screen. I removed anything that explained too much or broke the atmosphere. The aim was to create quiet tension. A room that never says something is wrong, but still makes you feel it.

Figma patterns creations

First setup with Shapes XR

Planning in Shapes XR

Final design

First interactions

Final Output

The final result was a VR prototype built in ShapesXR, designed as a familiar but uneasy job interview scene. The experience was built around fragments a missing application alert, a voice message, and personal details hinting at life beyond the room. Alongside the prototype,

I created a short teaser video that connects the project’s main themes: interior scenes, interface moments, and text fragments.

Editing the teaser helped me see the sequence more clearly what appears first, what carries emotional weight, and how tension builds. It also worked as a quick validatio

Strangers

at home

This was my first time designing for VR. A lot of things felt unfamiliar at the start how to pace interaction, how space affects focus, and how to build meaning without explanation.

I learned how to work within XR constraints and how small details in space can carry emotional weight when placed with care.

Looking back, I would test more even on paper to check which parts actually work and which are unnecessary. The process showed me that storytelling through space doesn’t have to be loud. Quiet tension can speak just as clearly.

Inspiration

Narative research

Scene selections

Prototyping in virtual space

I wanted to follow the spirit of We Are Live Here, with no dialogues and a space that communicates through its environment. I began by building a simple test scene in ShapesXR to understand how elements behave in space, how different interactions feel such as clicking or gaze, and what naturally draws or shifts attention. ShapesXR let me quickly test layouts and interaction flows without focusing on visual fidelity.

I explored several scene ideas, but the job interview stood out as structured, familiar, and full of unspoken expectations. I designed the space so the user uncovers key moments gradually. A note on the desk. A voice message. A fragment of conversation. An alert on the screen. I removed anything that explained too much or broke the atmosphere. The aim was to create quiet tension. A room that never says something is wrong, but still makes you feel it.

Final Output

The final result was a VR prototype built in ShapesXR, designed as a familiar but uneasy job interview scene. The experience was built around fragments a missing application alert, a voice message, and personal details hinting at life beyond the room. Alongside the prototype,

I created a short teaser video that connects the project’s main themes: interior scenes, interface moments, and text fragments.

Editing the teaser helped me see the sequence more clearly what appears first, what carries emotional weight, and how tension builds. It also worked as a quick validatio

Strangers

at home

This was my first time designing for VR. A lot of things felt unfamiliar at the start how to pace interaction, how space affects focus, and how to build meaning without explanation.

I learned how to work within XR constraints and how small details in space can carry emotional weight when placed with care.

Looking back, I would test more even on paper to check which parts actually work and which are unnecessary. The process showed me that storytelling through space doesn’t have to be loud. Quiet tension can speak just as clearly.

Prototyping in virtual space

I wanted to follow the spirit of We Are Live Here, with no dialogues and a space that communicates through its environment. I began by building a simple test scene in ShapesXR to understand how elements behave in space, how different interactions feel such as clicking or gaze, and what naturally draws or shifts attention. ShapesXR let me quickly test layouts and interaction flows without focusing on visual fidelity.

I explored several scene ideas, but the job interview stood out as structured, familiar, and full of unspoken expectations. I designed the space so the user uncovers key moments gradually. A note on the desk. A voice message. A fragment of conversation. An alert on the screen. I removed anything that explained too much or broke the atmosphere. The aim was to create quiet tension. A room that never says something is wrong, but still makes you feel it.

Final Output

The final result was a VR prototype built in ShapesXR, designed as a familiar but uneasy job interview scene. The experience was built around fragments a missing application alert, a voice message, and personal details hinting at life beyond the room. Alongside the prototype,

I created a short teaser video that connects the project’s main themes: interior scenes, interface moments, and text fragments.

Editing the teaser helped me see the sequence more clearly what appears first, what carries emotional weight, and how tension builds. It also worked as a quick validatio

Strangers

at home

This was my first time designing for VR. A lot of things felt unfamiliar at the start how to pace interaction, how space affects focus, and how to build meaning without explanation.

I learned how to work within XR constraints and how small details in space can carry emotional weight when placed with care.

Looking back, I would test more even on paper to check which parts actually work and which are unnecessary. The process showed me that storytelling through space doesn’t have to be loud. Quiet tension can speak just as clearly.

FAQ.

Clarifying Deliverable's Before They Begin

with Real Process and Honest アンサー.

01

What services do you offer?

02

What is your typical turnaround time?

03

Do you only work in Framer?

04

Can you handle both design and build?

05

Do you offer brand strategy too?

06

What’s your process like?

What services do you offer?

What is your typical turnaround time?

Do you only work in Framer?

Can you handle both design and build?

Do you offer brand strategy too?

What’s your process like?

What services do you offer?

What is your typical turnaround time?

Do you only work in Framer?

Can you handle both design and build?

Do you offer brand strategy too?

What’s your process like?